What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

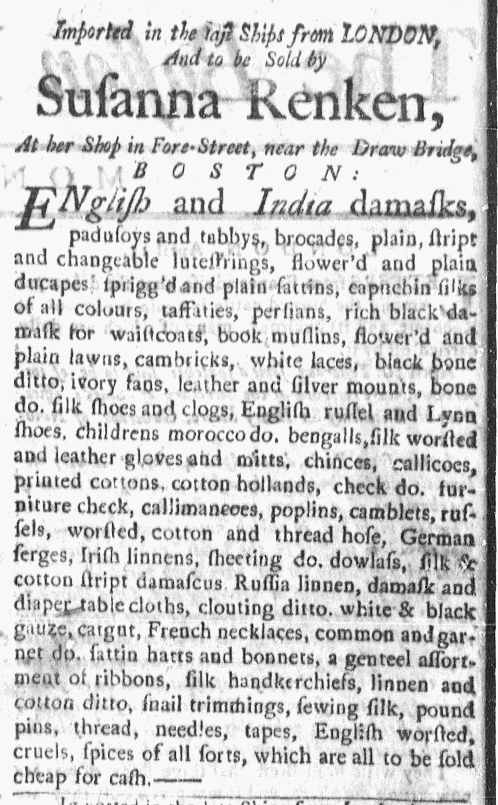

“To be Sold by Susanna Renken, At her Shop in Fore-Street.”

Susanna Renken was one of several women who took to the pages of the several newspapers published in Boston to advertise the assortment of seeds she stocked and sold in late winter and early spring in the late 1760s. In February 1768 she commenced this annual ritual among the sisterhood of the city’s seed sellers. Over the course of the next couple of weeks Rebeckah Walker, Bethiah Oliver, Elizabeth Clark, and Lydia Dyar and the appropriately named Elizabeth Greenleaf also inserted their own advertisements. As had been the case in previous years, their notices sometimes comprised entire columns in some newspapers, a nod towards classification in an era when printers and compositors exerted little effort to organize advertisements according to their content or purpose.

Even though some of these female seed sellers indicated that they sold other goods, usually grocery items, most did not intrude in the public prints to promote themselves in the marketplace throughout the rest of the year. They published their advertisements for seeds for a couple of months and then disappeared from the advertising pages until the following year. Susanna Renken was one of the few exceptions to that trend. Her advertisement for seeds concluded with brief mention of her other wares: “ALSO,–English goods, China cups and saucers, to be sold cheap for cash.” Nearly four months later she followed up with a much more extensive advertisement that listed dozens of items available at her shop, an advertisement that replicated those placed by other shopkeepers – male and female – who did not sell seeds (or, at least, did not promote seeds as their primary commodity in other advertisements).

What explains the difference between the strategies adopted by Renken and other female seed sellers? Did Renken better understand the power of advertising than her peers? After all, in addition to being one of the few to place additional notices she was the first to advertise in 1768, suggesting some understanding of being the first to present her name to the public that year. Was she more convinced than the others that advertising yielded a return on her investment that made it profitable to budget for additional notices? Alternately, Renken may have diversified her business more than other female seed sellers. She may have stocked a much more extensive inventory of imported dry goods than competitors who carried primarily seeds and groceries and perhaps a limited number of housewares. If that were the case, Renken may have earned a living as a “she-merchant” throughout the year while other female seed sellers participated almost exclusively in that trade and did not need to advertise during other seasons.

It is impossible to reconstruct the complete story of what distinguished Renken and her entrepreneurial activities from the enterprises of Clark, Dyar, Greenleaf, and other female seed sellers by consulting their advertisements alone. Many of those who trod the streets of Boston in the 1760s, however, would have possessed local knowledge that provided sufficient context for better understanding why Renken inserted addition advertisements and her competitors were silent throughout most of the year, especially if Renken continuously operated a shop with an assortment of merchandise and the others pursued only seasonal work when the time came to distribute seeds to farmers and gardeners.