What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“WANTED, by Lord N—, a good Head. The one he possesses at present, unwieldy, and heavy, and is of little Use to the Owner.”

Printers, authors, and others sometimes played with advertisements, adapting the format for unintended ends. In recent weeks, the Adverts 250 Project has examined purported advertisements that delivered opinions about society and politics, made all the more powerful because they initially looked like they had been placed for one purpose but upon closer examination achieved another. On November 22, 1773, for instance, the Pennsylvania Packet published more than a dozen advertisements submitted by an anonymous correspondent who believed that genre could be better perfected by extending them “to more of the different arts, professions, wants, losses, &c. of mankind.” Several other newspapers subsequently reprinted the letter from the correspondent and the advertisements. A few weeks later, the Connecticut Gazette carried a “WANTED” advertisement that described an ideal husband. While several of the advertisements in the piece in the Pennsylvania Packet critiqued women, this notice instead lectured men on how they should treat women.

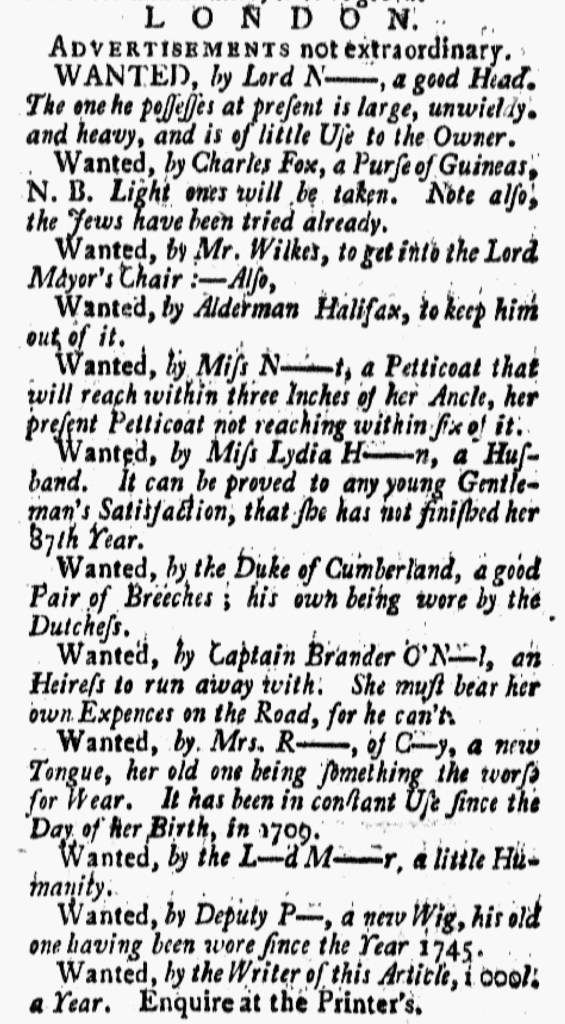

As a transition between news, much of it about the crisis over tea, and advertising, the December 24, 1773, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette published “ADVERTISEMENTS not extraordinary,” all of them “wanted” notices supposedly reprinted from newspapers in London. Like the advertisements in the Pennsylvania Packet, this collection included some that expressed political views and others that provided social commentary. In this instance, each of them invoked or alluded to the name of a real person, someone prominent enough that readers in England and the colonies would have recognized them. The first advertisement proclaimed, “WANTED, by Lord N—, a good Head. The one he possesses at present, unwieldy, and heavy, and is of little Use to the Owner.” Readers did not need Lord North’s full name to recognize a jab at the prime minister. Another advertisement stated, “Wanted, by the Duke of Cumberland, a good Pair of Breeches; his own being wore by the Dutchess.” The writer apparently considered it well known that the duchess did not abide by her expected role but instead ruled her husband. Yet another scolded a woman who did not demonstrate appropriate decorum in how she dressed. “Wanted, by Miss N—t,” it declared, “a Petticoat that will reach within three Inches of her Ancle, her present Petticoat not reaching within six of it.” The litany of advertisements concluded with one placed by the author: “Wanted, by the Writer of this Article, 1000l. a Year. Enquire at the Printer’s.” Those final instructions echoed the directions given in so many advertisements. Printers often served as intermediaries who supplied additional information beyond what appeared in the advertisements published in their newspapers. These “ADVERTISEMENTS not extraordinary” provided a platform for the anonymous author to become a pundit, each notice making a biting remark about contemporary politics and culture.