What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A neat BOAT, suitable for the reception of passengers.”

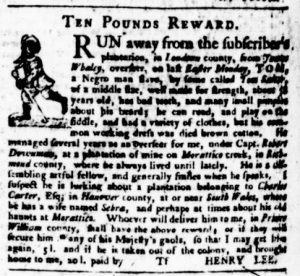

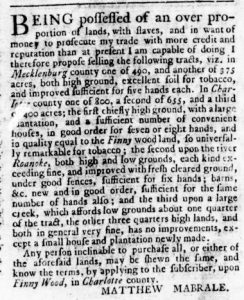

Readers encountered four advertisements for transportation via “Passage Boat” in the June 30, 1769, edition of the New-London Gazette. Ebenezer Webb sailed between New London and Sterling on Long Island “as usual,” though he advised prospective passengers that they “may be landed on any Part of the East End of the Island.” Peter Griffing charted a similar course across Long Island Sound, but kept a different schedule than his direct competitor, Webb. A brief advertisement reminded readers that “Truman’s Passage-Boat plies between Sagharbour and Norwich Landing, as usual.”

Samuel Stockwell inserted a much more extensive advertisement to address prospective passengers; it occupied as much space on the page as the other three advertisements combined. Unlike the others, Stockwell did not transport passengers and freight across Long Island Sound. Instead, he sailed up and down the Thames River between New London and Norwich. In order to pursue that enterprise, he had “lately built and has now fitted out a neat BOAT, suitable for the reception of passengers.” In a nota bene, he added that he provided food and wine “at a very reasonable rate.”

Griffing, Truman, and Webb did not comment on why readers of the New-London Gazette might wish to travel aboard their passage boats except to move freight and passengers from one place to another. Each implied that crossing Long Island Sound was much more efficient than making a journey by land. Stockwell, on the other hand, suggested that “Gentlemen or Ladies” might wish to make a voyage aboard his boat “for their health or pleasure,” presenting his business as part of a nascent tourism and hospitality industry that began to emerge in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Realizing that passengers seeking leisure activities likely would not sustain his new endeavor by themselves, he also made a practical appeal to “Gentlemen that have occasion to attend the courts” when they were in session in New London and Norwich. Stockwell set a regular schedule, but he adapted during those weeks that prospective passengers needed to attend “the sitting of the courts.” Hiring passage on his boat, he proposed, would “lessen the vast expence of the law” by eliminating the “great expense of horse hire and keeping.” Even though less than fifteen miles separated New London and Norwich, those who traveled between the two incurred significant expenses if they made the journey on land. Stockwell provided an attractive and more comfortable alternative, one that made the journey a “pleasure” even for those who traveled to attend to business at the courts.