What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Printed CATALOGUES of the Library of the late Jeremy Gridley, Esq; will be delivered Gratis at the Auction Room.”

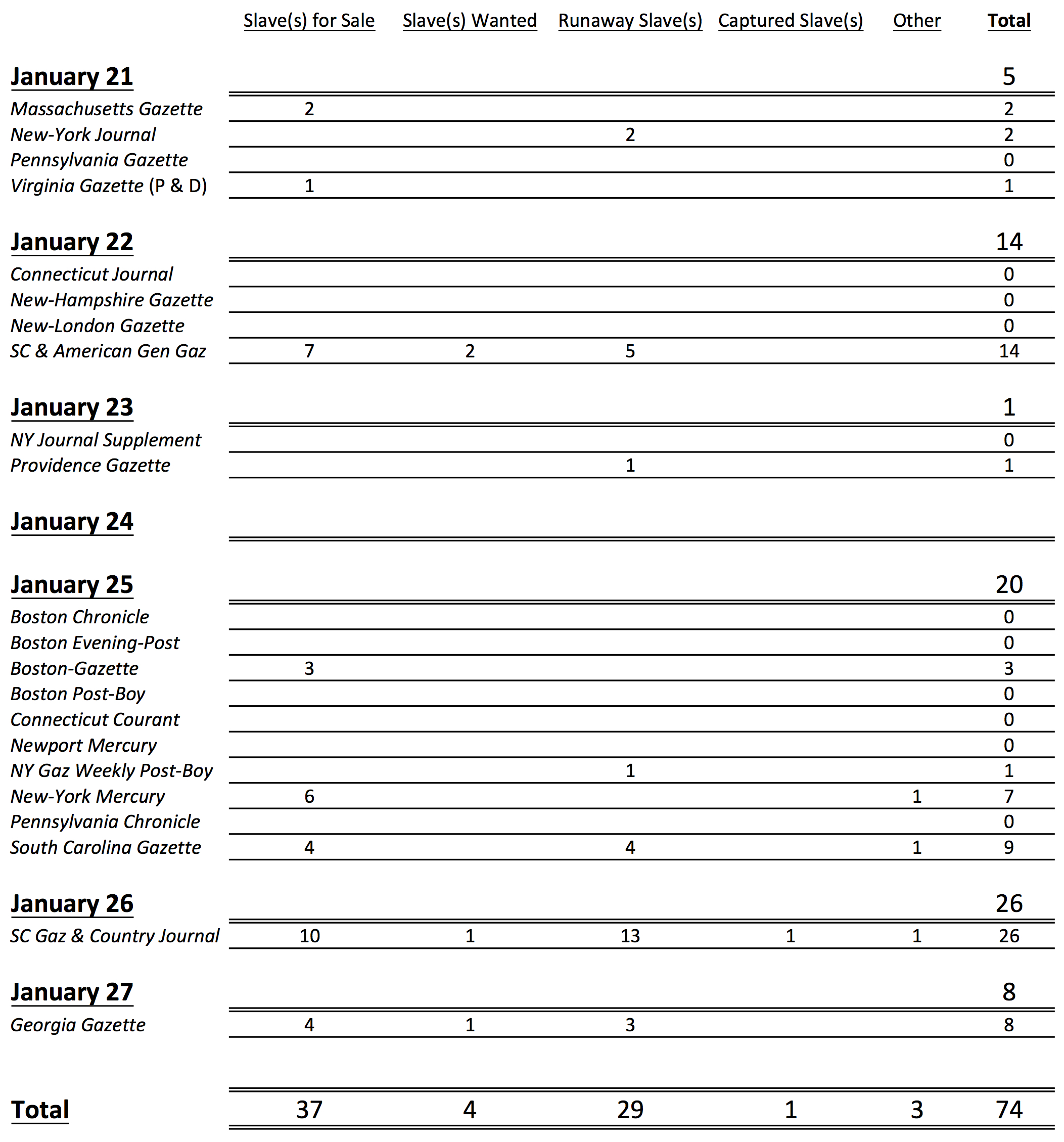

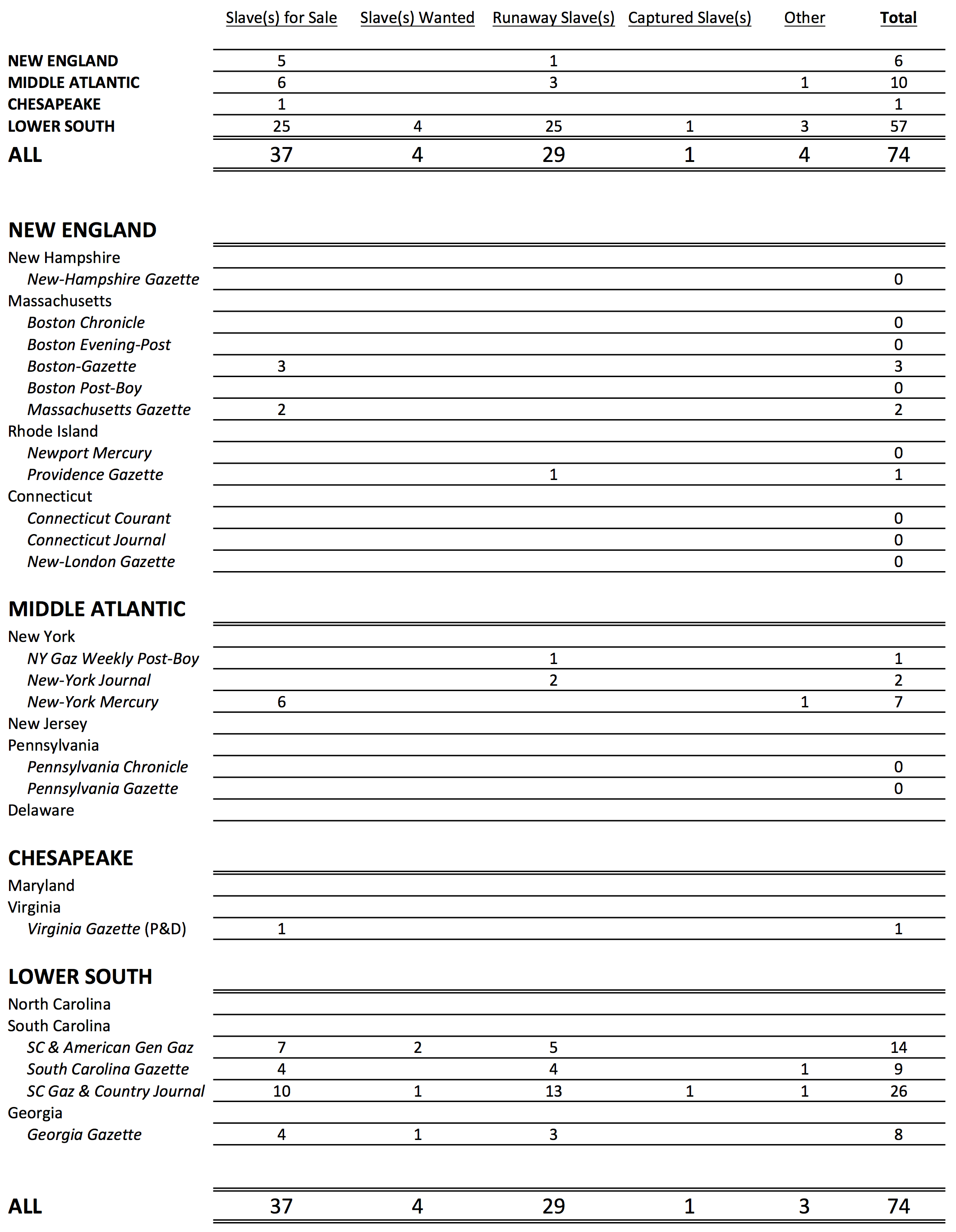

In January 1768 auctioneer Joseph Russell deployed multiple media in his efforts to promote a sale devoted to “The LIBRARY of the late Jeremy Gridley, Esq.” He first placed notices in most of the local newspapers, including advertisements that ran in the Massachusetts Gazette on January 21 and in the Boston Evening-Post, the Boston-Gazette, and the Boston Post-Boy on January 25. (He did not place a similar advertisement in the Boston Chronicle. That newspaper had commenced publication only a few months earlier. It featured very few advertisements, an indication that it had not yet attracted significant distribution or readership. Russell may not have considered advertising in that newspaper likely to produce a return on his investment.) Each of these advertisements informed residents of Boston and its environs that Gridley’s library consisting of books on “LAW, HISTORY, DIVINITY, &c.” would be sold “by PUBLIC VENDUE, at the Auction Room in Queen-Street” on the morning of Tuesday, February 2. Notices appeared in multiple newspapers early enough for interested parties to plan to attend the auction.

Russell’s advertisement appeared in the Massachusetts Gazette once again on January 28, but this time a second notice on another page supplemented it. That advertisement announced that “printed CATALOGUES of the Library of the late Jeremy Gridley, Esq; will be delivered Gratis at the Action Room” on the day before the auction. The February 1 editions of the other newspapers that carried Russell’s advertisement each updated Russell’s earlier advertisement with some variation that noted readers could obtain an auction catalog for free. The notice in the Boston Evening-Post, for instance, featured at manicule directing attention to “Printed Catalogues may be had at the Auction-Room, gratis.” Russell used one medium to incite interest not only in the books for sale but also to incite interest in another medium marketing those books.

Newspaper notices and auction catalogs may not have been the only advertising media Russell used to garner attention for an upcoming auction. He may have also distributed handbills or posted broadsides around town. Evidence of the auction catalogs appears in his newspaper advertisements even if none of the catalogs survived, but other ephemeral marketing materials may have simply disappeared after the auction. At the very least, Russell’s original and updated advertisements in four newspapers in combination with his auction catalog suggest a coordinated and extensive effort to attract attention and, ultimately, bidders at the sale of Gridley’s library.