What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

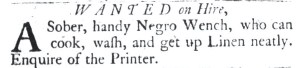

“(T. b. c.)”

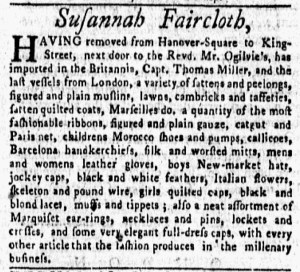

For eight weeks in the fall of 1771, George Olney ran an advertisement for a “compleat Assortment of English and India GOODS” in the Providence Gazette. His advertising campaign commenced on October 12 and concluded on November 30. From week to week, an identical notice appeared in the public prints, with one exception. The last four insertions included an additional line with a notation, “(T. b. c.),” that was not part of the original advertisement. Readers likely passed over that notation, realizing that it was intended for the compositor and other workers in John Carter’s printing office.

Similar notations appeared at the end of advertisements in many colonial newspapers, many of them listing issue numbers that corresponded to the first and last appearance so compositors could easily determine whether to include advertisements when preparing the next edition. Other notations require more systematic attention to multiple advertisements published over the course of weeks or months to decode. What did “(T. b. c.)” mean? Perhaps it meant “to be continued” until the advertiser decided to discontinue the notice. In that case, Olney likely initially paid to have his advertisement run for four weeks and then requested that it continue until he instructed otherwise. That, however, would have run contrary to the policy that Carter stated in the colophon: “ADVERTISEMENTS of a moderate Length (accompanied with the Pay) are inserted in this Paper three Weeks for Four Shillings Lawful Money.” Carter did not seem inclined to extend credit to advertisers, but the notation on Olney’s advertisement suggests that the printer may have exercised some discretion for those who paid for an initial run.

Consulting ledgers and account books might reveal practices in the printing office that deviated from the policy in the colophon, but in their absence an examination of other advertisement with the same notation might establish a pattern. Other advertisements in the Providence Gazette bore the “(T. b. c.)” notation. Next week, the Adverts 250 Project will examine another of those advertisements to determine when in its run it acquired the notation. That may help to outline some of the likely business practices adopted by Carter as he managed advertising in his newspaper.