What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Compleat Assortment of Stationary Ware, consisting of almost every Article in that Branch.”

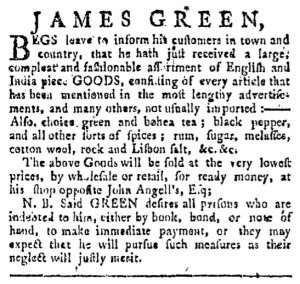

George Wood, “STATIONER and BOOKBINDER in Elliott-street” in Charleston, adopted many of the marketing appeals most frequently used by merchants and shopkeepers who sold dry goods and housewares in eighteenth-century America. In particular, he emphasized consumer choice when he noted that he stocked “a very large and compleat Assortment of Stationary Ware” and then listed dozens of specific items. His inventory included everything from the basics, like “Writing Paper of all Kinds” and “best London Ink Powder,” to specialty items, like “large Ink Pots for Compting-Houses” and Surveyors Pocket Cases of Instruments.” To guarantee that potential customers did not assume that he sold only the items listed in his advertisement, Wood concluded his list with “&c.” (the eighteenth-century abbreviation for et cetera), allowing readers to conjure up images of other stationery wares that might be in Wood’s shop.

He followed a similar strategy in listing books he had for sale, listing some of the most popular titles before making nods toward general categories, such as “a great Variety of small Picture Books for Children” and “a great Variety of Song Books.” Just in case readers did not notice particular titles they desired, Wood doubled down on his appeal to consumer choice: “He has likewise to dispose of, upwards of One Thousand Volumes of curious Books, consisting of Histories, Voyages, Travels, Lives, Memoirs, Novels, Plays, &c.” The bookseller had something for every taste and interest. Customers just needed to visit his shop and explore the shelves to find the books they wanted.

Wood realized schoolmasters in particular would likely be interested in the variety of titles he stocked, especially spelling and math books. He indicated that some volumes were intended “for the use of Schools.” To encourage instructors to choose from among his selection, Wood offered discounts if they would “take a Quantity” to distribute among their students.

By offering such a “large and compleat Assortment” of stationery, writing supplies, and books, Wood encouraged customers of all sorts to visit his shop. Providing a list of merchandise not only underscored consumer choice but also allowed him to identify specific types of customers with particular interests or specialized needs. His advertisement addressed the general interests of colonial readers, but also marketed certain wares to several occupational groups.