What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

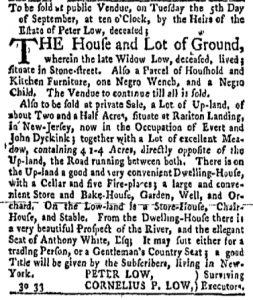

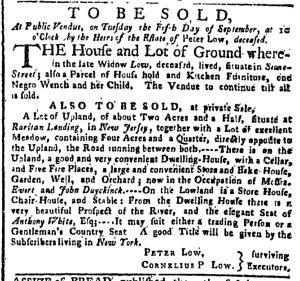

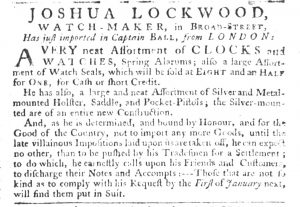

The August 31, 1769, edition of Richard Draper’s Massachusetts Gazette included several advertisements for consumer goods. John Gerrish advertised a “very large Assortment of Goods, and Merchandize.” Other advertisers specialized in retail sales of particular kinds of goods: Zechariah Fowle advertised books, Peter Roberts “Drugs & Medicines,” and Richard Smith spermaceti candles “Manufactured by Daniel Jenckes & Com. at Providence.” Other advertisers promoted upcoming auctions, such as Joseph Russell’s notice for a “Variety of Houshold Furniture” intended for sale “by PUBLIC VENDUE” a week later. Still others announced estate sales, giving readers an opportunity to purchase secondhand goods.

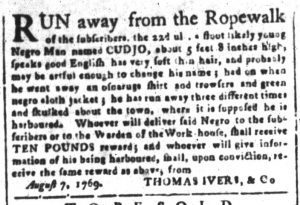

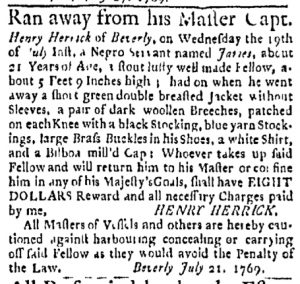

Yet retail sales, auctions, and estate sales were not the only means of acquiring goods and participating in the consumer revolution that was taking place in the colonies and throughout the British Atlantic world. Another advertisement reported that someone “broke open and rob’d” the store belonging to Benjamin Greene and Son earlier in the month. Several pieces of merchandise went missing, including handkerchiefs, sewing silk, “Mens Hose,” and assorted textiles. Greene and Son offered a reward to “Whoever will discover the Thieves so that they may be brought to Justice.”

Unfortunately for retailers and residents of Boston and other cities and towns throughout the colonies, Greene and Son’s advertisement was not particularly unusual. Similar advertisements appeared regularly in the public prints, suggesting that those who could not participate in consumer culture through legitimate means resorted to other methods of acquiring the goods they desired. The “sundry small Articles” taken from Greene and Son’s store likely ended up in the hands of colonists other than the thieves, passing through a black market or, as Serena Zabin has termed it, an “informal economy” for distributing goods of questionable provenance. The reach of the consumer revolution extended far beyond the gentry and the middling sort; it encompassed colonists of all backgrounds. Those who lacked the means to visit the shops, auction houses, and estate sales advertised in the Massachusetts Gazette and other newspapers devised other ways of obtaining consumer goods.