GUEST CURATOR: Nicholas Sears

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

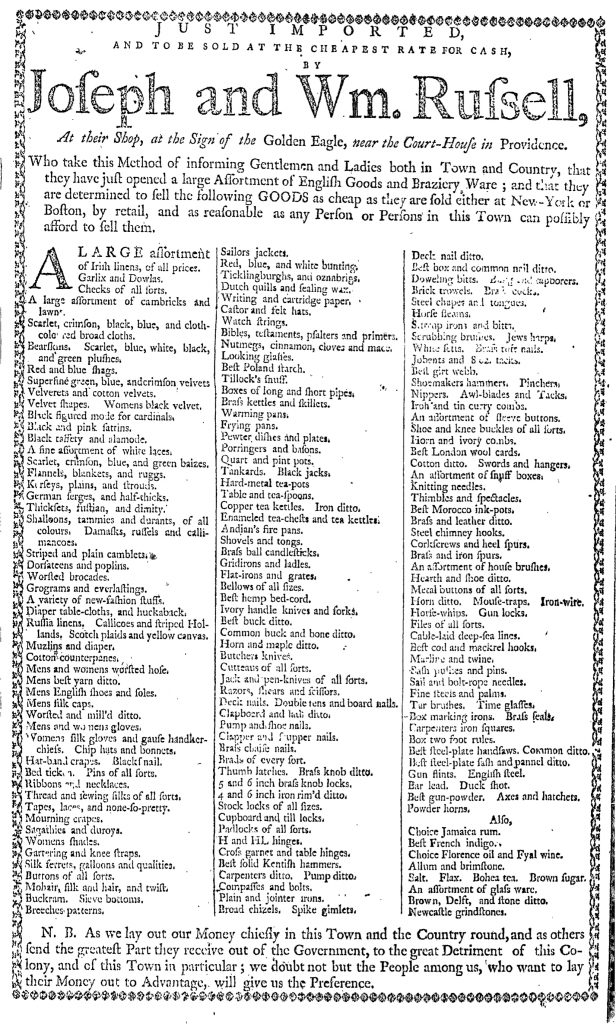

“JUST IMPORTED … silk and worsted mitts … silk knee straps … sewing silk of all coulours.”

James Green’s advertisement was full of different types of clothes, clothing accessories, and types of fabric to make clothes, including cotton, velvet, linen, and silk. What caught my attention was the amount of silk clothing and accessories that came over from England. It caused me to ask, “Why were there so many items made of silk coming from England?” I was curious whether the English imported clothing made with silk themselves and then shipped it to the colonies or if they made it themselves.

I read Gerald B. Hertz’s article discussing “The English Silk Industryin the Eighteenth Century.”[1] According to Hertz, England had its own silk weavers, comprised mainly of Flemish refugees in the early seventeenth century. It was not until 1685 when Huguenots, a Protestant group from France, started to emigrate to England that the amount of silk produced rose. Even with the silk industry rising, there was still a large amount of silk being imported from other countries. To combat this, England continued to pass laws that prohibited the importing of manufactured silk items from 1765 to 1826. In 1780 the annual import of raw silk rose to 200,000 pounds and later to 500,000 pounds after 1800.[2] England also tried to produce raw silk in their American colonies, specifically Georgia, but abandoned that plan after 1742.

The amount of silk items shipped to the English colonies rose during the consumer revolution, which in turn helped the economy of England.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

According to his advertisement, James Green’s shop was located “at the Sign of the Elephant, opposite JOHN ANGEL’s, Esq.” Eighteenth-century shop signs often incorporated animals and birds of various sorts. In choosing the elephant as the device to identify his business, Green prompted potential customers to associate the goods he stocked with exotic and faraway places. The elephant conjured images of some of the lands where raw silk was produced and acquired by European merchants in the eighteenth century.

Nick notes two overlapping streams of silk production that eventually entered colonial markets. The first, raw silk, was a necessary resource for producing the second, manufactured silk goods. Nick focuses primarily on the English silk industry as it pertained to the production of manufactured goods that were then exported for colonists to purchase, often listed alongside the myriad of other goods increasingly on offer by merchants and shopkeepers as part of the consumer revolution.

To produce manufactured silk goods for export, the English silk industry needed raw silk. What were their sources in the eighteenth century? Hertz provides answers to that question as well. In the early eighteenth century, “Turkey and the Levant were most important,” Hertz explains.[3] The English silk industry used Turkish silk to produce silk stockings, damasks (figured woven fabrics with a pattern visible on both sides, typically used for table linen and upholstery), and galloons (narrow ornamental strips of fabric, typically a silk braid or piece of lace, used to trim clothing or finish upholstery). According to Hertz, “The Turkey Company’s most valued import was sherbaffee, fine raw silk from Persia.”[4] The English silk industry also obtained unwrought silk from Italy and India and elsewhere in the east. Over time, raw silk from India and China became one of the East India Company’s most important imports. As Nick notes, the English silk industry stood to benefit when colonists experimented with silk cultivation in Georgia when the colony was founded, but their efforts were largely unsuccessful and the endeavor concluded fairly quickly.

As a result, the raw silk transformed into manufactured goods continued to come primarily from places on the other side of the globe, like Turkey and India. In choosing the elephant to identify his shop, James Green evoked images of trade and exchange that were not merely transatlantic but global. Many of the items listed in his advertisement, including tea and spices as well as silk, came from places far beyond England and continental Europe. The “Sign of the Elephant” did more than identify Green’s shop. It also encouraged consumers to attribute meaning and value to the goods they purchased. Visiting a local shop could be as fun or adventurous as browsing through the markets in faraway places most colonists only encountered in stories and their imaginations.

**********

[1] Gerald B. Hertz, “The English Silk Industry in the Eighteenth Century,” English Historical Review 24, no. 96 (October 1909): 710-626.

[2] Hertz, “English Silk Industry,” 712.

[3] Hertz, “English Silk Industry,” 711.

[4] Hertz, “English Silk Industry,” 711.