What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Printed Proposals for taking in Subscriptions for Printing the ANSWER to De Laune’s Plea for the Non-Conformists.”

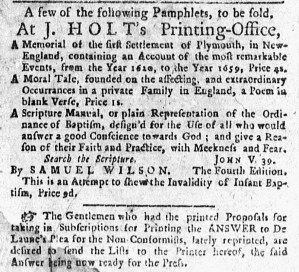

In addition to printing the New-York Journal, John Holt also sold imported books and printed and sold books and pamphlets. Following the example of other printer-booksellers in the colonies, he inserted advertisements in his own newspapers. Such was the case on January 28, 1773, when he advised readers of several pamphlets available at his printing office, including “A Memorial of the first Settlement of Plymouth in New-England.”

Holt also used that advertisement to pursue other business. He planned to print “the ANSWER to De Laune’s Plea for the Non-Conformists,” a work that he indicated had been “lately reprinted.” As part of that project, Holt distributed subscription notices that likely described the work, both its contents and the material aspects of the paper and type, and the conditions for subscribing, including prices and schedule for submitting payments. He provided these “printed Proposals for taking in Subscriptions” to associates who assisted in recruiting customers who reserved copies in advance. In some instances, subscribers made deposits as part of their commitment to purchasing a work once it went to press. Holt’s associates may have distributed subscription notices in the form of handbills or pamphlets to friends, acquaintances, and customers or posted them in the form of broadsides in their shops. Subscribers may have signed lists, perusing the names of other subscribers when they did so, or Holt’s associates may have recorded their names. Holt’s reference to “printed Proposals for taking in Subscriptions” did not offer many particulars.

Like many broadsides, handbills, trade cards, and other advertising ephemera that circulated in eighteenth-century America, Holt’s “printed Proposals for taking in Subscriptions” were discarded when no longer of use. Perhaps one or more copies have been preserved in research libraries or private collections, but they have not yet been cataloged. For now (and probably forever), a newspaper advertisement that makes reference to a subscription notice that circulated in New York in the early 1770s constitutes the most extensive evidence of its existence. As I have noted on several occasions, this suggests that early Americans encountered much more advertising, distributed via a variety of printed media, than historians previously realized … and much more than will ever be recovered.