What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

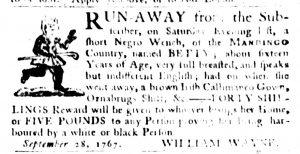

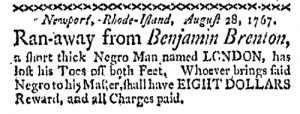

“RUN AWAY … a NEGROE FELLOW, named LONDON.”

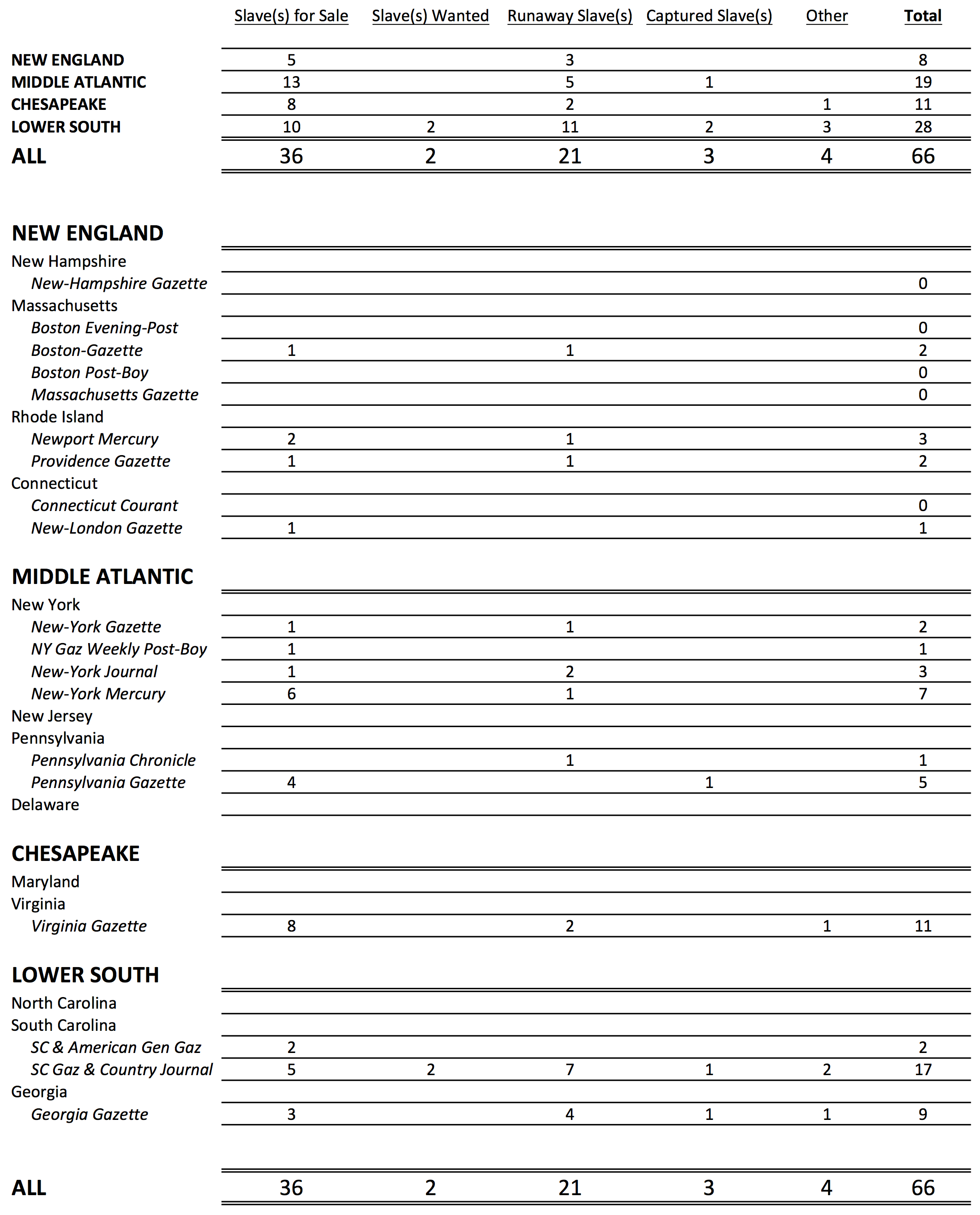

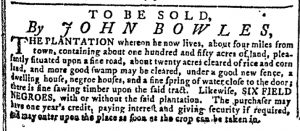

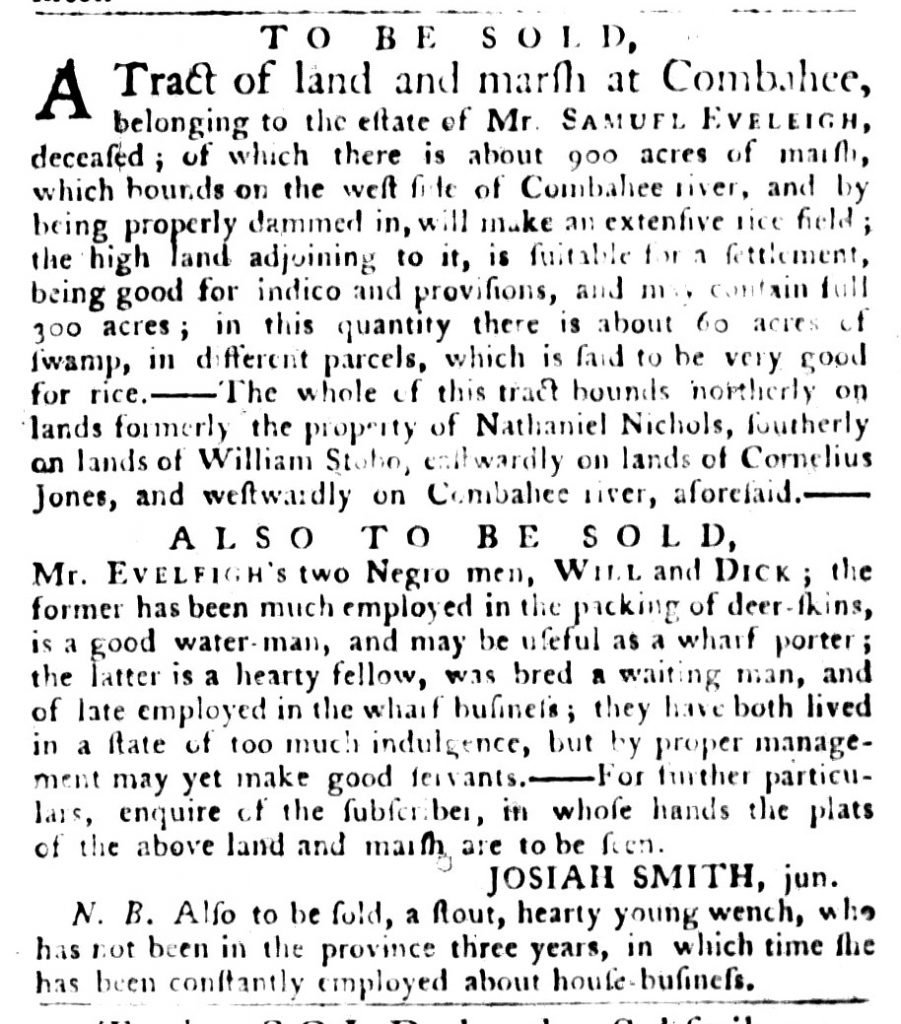

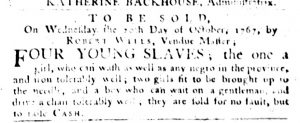

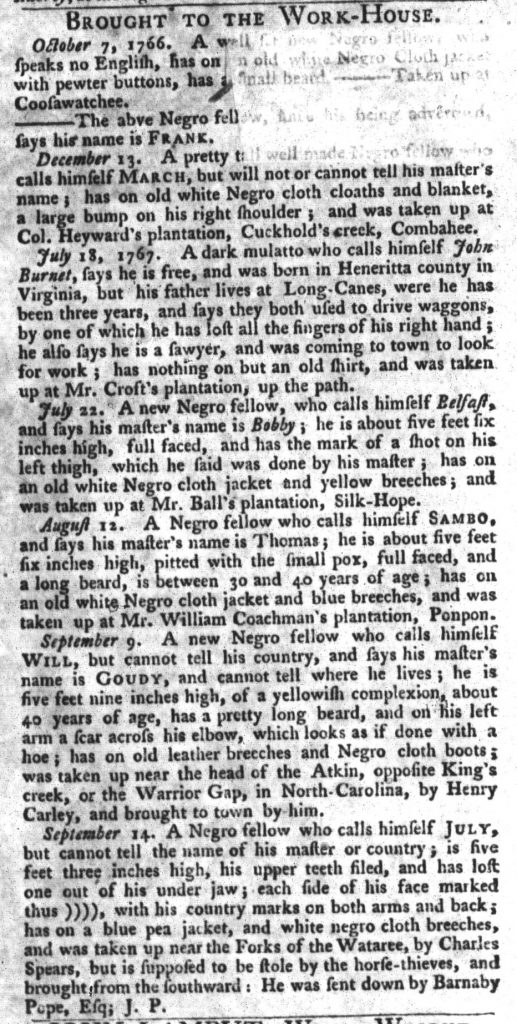

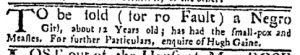

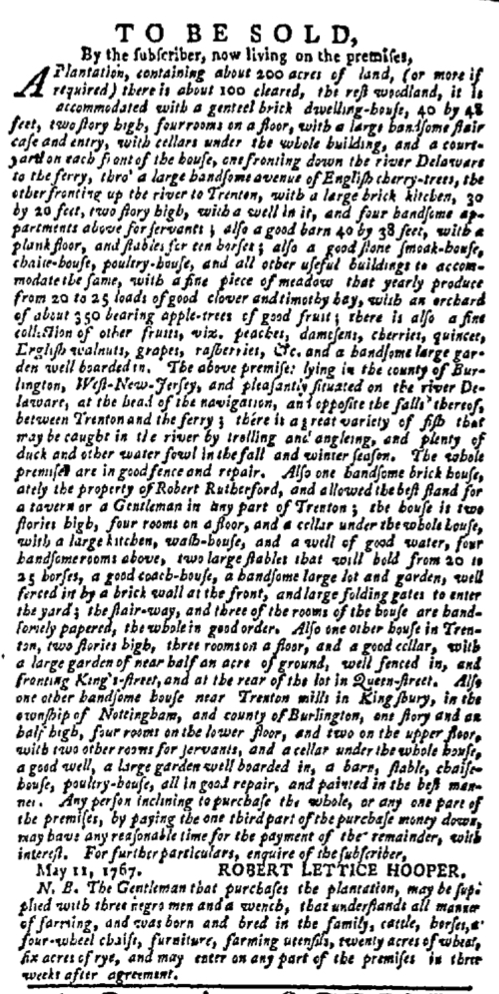

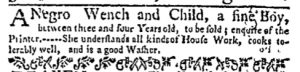

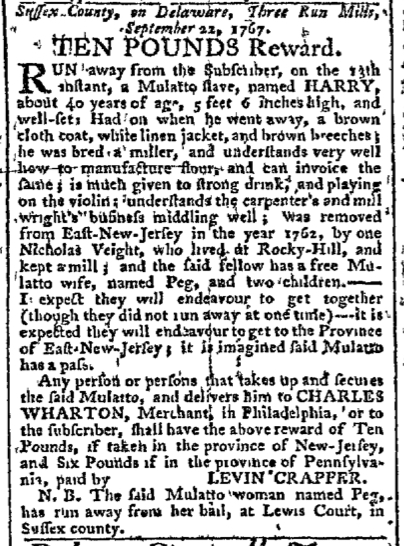

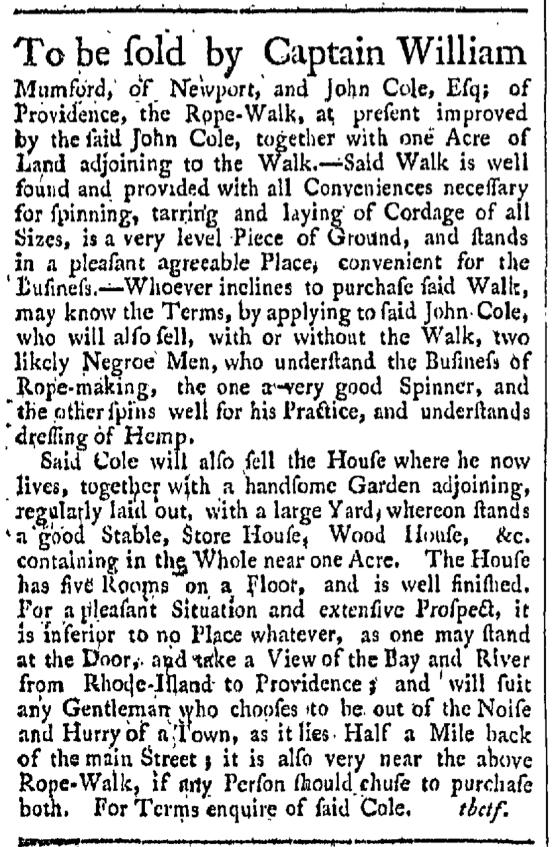

Hundreds of advertisements for runaway slaves appeared in colonial American newspapers every year throughout the 1760s, documenting one form of resistance to the institution of slavery. From New Hampshire to Georgia, readers would have recognized them as a familiar component of the public prints, published alongside advertisements for consumer goods and assorted legal notices. Many runaway advertisements focused solely on the experiences of particular runaways, but some also told stories about other members of colonial communities.

Grey Elliott inserted such an advertisement in the September 30, 1767, issue of the Georgia Gazette. In it, he reported that London, a “NEGROE FELLOW … well known in and about Savannah” ran away a month earlier. Elliott offered a reward, ten shillings, to whoever captured London and delivered him either to Elliott or “the Warden of the Work house in Savannah.” In addition, he detailed two other awards. Suspecting that London had assistance from accomplices, Elliott announced rewards for anyone “who shall discover him or her by whom the said negroe is harboured.” In other words, he was interested in learning where London was hiding out and who concealed him from his master and colonial authorities. The awards varied: “TWENTY SHILLINGS if a slave” (twice as much as the reward for capturing London) and “FIVE POUNDS … if a white person” (ten times as much as the reward for capturing the runaway). The wording makes it difficult to determine definitively if Elliott meant a slave informant would receive twenty shillings and a white one five pounds or of he meant that the rewards would depend on whether London received aid from a fellow slave or a white accomplice.

Either way, Elliott’s advertisement demonstrates that runaways did not always go it alone when they absconded from their masters. Instead, they benefited from assistance provided by other slaves and, perhaps, sometimes even sympathetic white colonists. Other runaway advertisements provided even more specific information, sometimes noting family relationships that might have drawn runaways to particular places or influenced others to provide aid and comfort. Running away was an act of resistance undertaken by many slaves, but it also had ripple effects. Those who provided assistance to runaways engaged in their own acts of resistance as member of a community allied against the power and authority of slaveholders.