What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

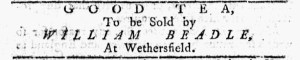

“GOOD TEA, To be Sold.”

William Beadle was at it again. He advertised “GOOD TEA, To be Sold by WILLIAM BEADLE, At Wethersfield” in the June 28, 1774, edition of the Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer. Unlike many other merchants and shopkeepers, Beadle had not refrained from advertising tea after colonizers disguised as Indians dumped tea into Boston Harbor on December 16, 1773. In March 1774, he advertised “Best Bohea TEA, Such as Fishes never drink!!” In April, he opened a new advertisement with a headline promoting “A New Supply of TEA, Extraordinary good.” Perhaps Beadle sold smuggled tea that evaded the duties imposed by Parliament but could not state that was the case in the public prints … or his politics did not align with the patriots who objected to Parliament regulating trade in the colonies … or he realized that many consumers still wished to drink tea even with the controversy swirling around that commodity.

Still, his latest advertisement hawking tea and only tea seemed especially bold. It was the first one he published after the Boston Port Act closed and blockaded the harbor until residents of that town paid for the tea that some of them destroyed. Word of that punishment arrived in the colonies in May, before the legislation went into effect on June 1. Newspapers throughout the colonies carried coverage of the Boston Port Act and reactions in Boston and other towns. Many people called for a new round of boycotts on goods imported from England, including tea. Further coverage focused on other measures meant to bring Boston in line, the series of Coercive Acts that included an Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice and a Quartering Act. The issue of the Connecticut Courant that ran Beadle’s advertisement featured “AnAUTHENTIC ACCOUNT” from London “of Friday’s DEBATE on the second Reading of the Bill regulating the civil government of the Massachusetts-Bay.” Known as the Massachusetts Government Act, that legislation abrogated the colony’s charter from 1691 and gave new powers to the royal governor. That same issue included updates from Boston and, on the same page as Beadle’s advertisement for tea, a “Copy of a Letter from the Committee of Correspondence in New-York, to the Committee in Boston.” Yet not everyone held what seemed to be the prevailing political sentiments captured in the public prints. Even as John Holt swapped out the British coat of arms for the severed snake representing American unity in the masthead of the New-York Journal, some merchants and shopkeepers, such as William Beadle, continued advertising tea rather than making pronouncements about abstaining from the beverage due to political principles.