What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

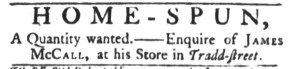

“HOME-SPUN, A Quantity wanted.”

In so many ways, James McCall’s advertisement appeared as a stark contrast compared to others in the September 27, 1774, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. In just three lines, it proclaimed, “HOME-SPUN, A Quantity wanted. – Enquire of JAMES McCALL, at his Store in Tradd-street.” The word “HOME-SPUN” in all capitals in a significantly larger font occupied a line on its own, calling attention to the commodity that McCall sought. He referred to linen and wool textiles produced in the colonies as an alternative to imported fabrics. Spinning, a domestic chore undertaken by women, took on political significance when colonizers enacted nonimportation agreements in response to the duties imposed in the Townshend Acts in the late 1760s. The homespun cloth that resulted from their efforts became a visible symbol of support for the Patriot cause. McCall did not need to elaborate on the political principles associated with homespun when he placed his advertisement seeking a quantity of it. In other advertisements, he had previously demonstrated that how well he understood consumer politics.

Elsewhere in the same issue of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, merchants who imported “fashionable” textiles from London and other English ports ran lengthy advertisements that listed and described their merchandise. Edwards, Fisher, and Company, for instance, ran their notice about receiving “PART of their FALL GOODS.” Mansell and Corbett inserted an even more lengthy advertisement that featured imported fabrics, emphasizing “the most fashionable colours” and “an entire new pattern,” as well as housewares. Other advertisers were a bit more restrained in terms of length, but not their exuberance for imported textiles. In addition to leading his list of merchandise with a “LARGE Assortment of printed Muslins, Linens, and Calicoes,” Z. Kingsley concluded with a nota bene that explained, “The printed Muslins and Linens, are all the newest Patterns.” These merchants considered it necessary to offer assurances to prospective customers that their wares did indeed follow the latest styles, simultaneously emphasizing all the choices available to them. Homespun cloth, on the other hand, turned fashion on its head. What was the newest and the most sophisticated did not matter as much as the simple political message that producing, purchasing, and wearing homespun communicated during the imperial crisis.

[…] In so many ways, James McCall’s advertisement appeared as a stark contrast compared to others in the September 27, 1774, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. In just three lines, it proclaimed, “HOME-SPUN, A Quantity wanted. – Enquire of JAMES McCALL, at his Store in Tradd-street.” The word “HOME-SPUN” in all capitals in a significantly larger font occupied a line on its own, calling attention to the commodity that McCall sought. He referred to linen and wool textiles produced in the colonies as an alternative to imported fabrics. Spinning, a domestic chore undertaken by women, took on political significance when colonizers enacted nonimportation agreements in response to the duties imposed in the Townshend Acts in the late 1760s. The homespun cloth that resulted from their efforts became a visible symbol of support for the Patriot cause. McCall did not need to elaborate on the political principles associated with homespun when he placed his advertisement seeking a quantity of it. In other advertisements, he had previously demonstrated that how well he understood consumer politics. Elsewhere in the same issue of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, merchants who imported “fashionable” textiles from London and other English ports ran lengthy advertisements that listed and described their merchandise. Read more… […]