What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“It is probable a non-importation agreement may be soon entered into by the colonies.”

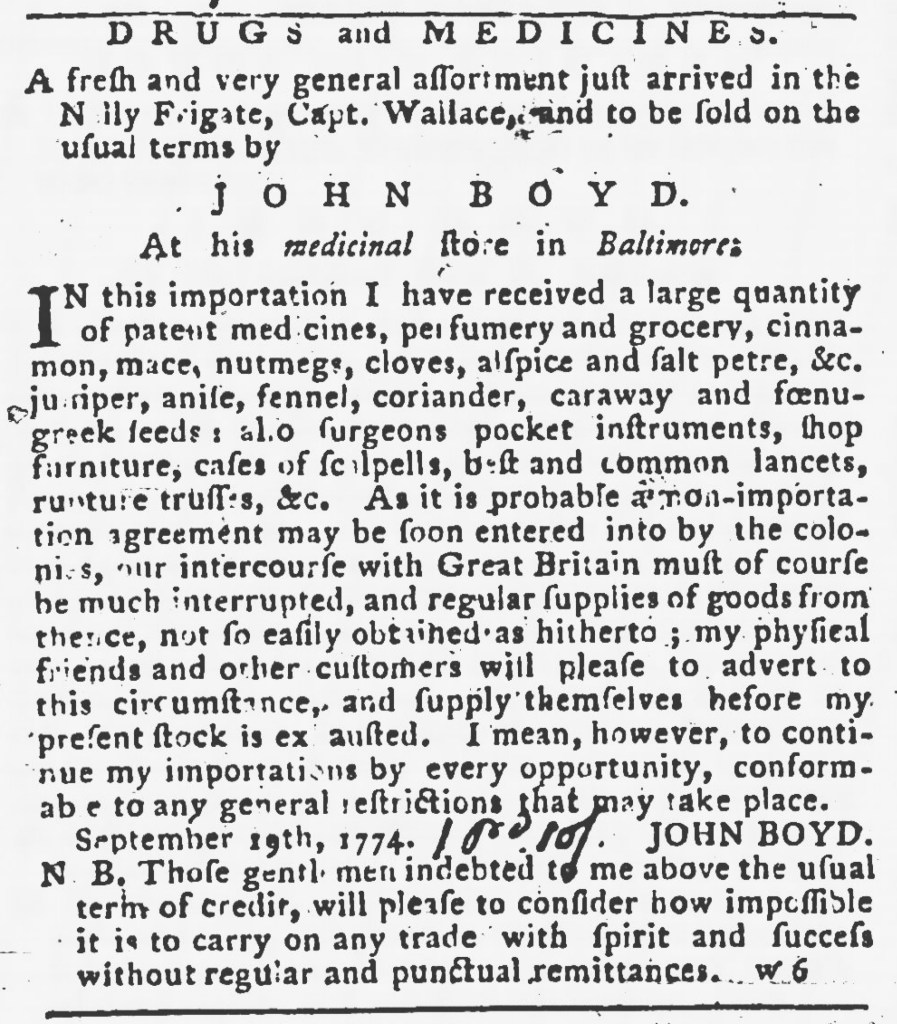

In the fall of 1774, John Boyd advertised the “DRUGS and MEDICINES” available at “his medicinal store in Baltimore” in both the Maryland Gazette, published in Annapolis, and the Maryland Journal, published in Baltimore. The latter was still so new that the apothecary realized many of his prospective customers still relied on the former as their local newspaper. He reported that he just imported a “fresh and very general assortment” of patent medicines, “perfumery and grocery” items, spices, and medical equipment.

Boyd also leveraged current events in hopes of moving his merchandise. At that moment, the First Continental Congress was meeting in Philadelphia, deliberating over responses to the Coercive Acts passed after the Boston Tea Party. He reminded readers that “it is probable a non-importation agreement may be soon entered into by the colonies” and when that happened “our intercourse with Great Britain must of course be much interrupted, and regular supplies of goods from thence, not so easily obtained as hitherto.” That being the case, he advised doctors, his “physical friends,” and his other customers to “supply themselves before my present stock is exhausted.” In other words, they needed to make purchases while the items they needed or wanted were still available. A boycott would result in scarcity and, eventually, empty shelves, storerooms, and warehouses. Boyd was not the only entrepreneur making that argument. In Charleston, Samuel Gordon recommended to “the Ladies” that they needed to buy his textiles, accessories, and housewares while supplies lasted because “a Non-importation Agreement will undoubtedly take Place here.” Boyd’s advertisement made clear that it was not solely “the Ladies” who needed to worry about politics causing disruptions in the marketplace.

He vowed to do what he could to limit the effects, stating that he would “continue my importations by every opportunity,” though he carefully clarified that he would do so “conformable to any general restrictions that may take place.” He would continue accepting shipments for as long as possible, replenishing his stock to ward off scarcity, yet there would come a time that he would have to yield to whatever agreement colonizers adopted. His advertisement preemptively suggested to prospective customers that they should check with him when they discovered that other apothecaries no longer stocked their usual wares. Colonizers had experienced nonimportation twice in the past decade, first in response to the Stamp Act and later in response to the duties on certain imported goods in the Townshend Acts. Savvy entrepreneurs like Boyd reminded them how to prepare for what looked to be inevitable disruptions.