What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The publisher would be very glad to have some more good original pieces handed to him.”

When Joseph Greenleaf ceased publication of the Royal American Magazine just after the battles at Lexington and Concord, Robert Aitken’s Pennsylvania Magazine, Or American Monthly Museum became the only magazine published in the American colonies. Circumstances in Boston prevented Greenleaf from continuing production of his magazine, acquired from its founder, Isaiah Thomas, the previous summer. Aitken had a more advantageous situation in Philadelphia.

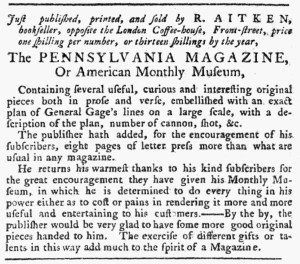

Yet events unfolding in Massachusetts loomed large for Aitken and readers of the Pennsylvania Magazine. When Samuel Loudon, a bookseller in New York, advertised subscriptions for the magazine in August 1775, he noted that the most recent issue came with a bonus item, a “new and correct Plan of the TOWN of BOSTON, and PROVINCIAL CAMP.” Aitken highlighted coverage of the siege of Boston and the threat posed by British troops in his own advertisements. In early September, he informed the public that the contents of the most recent issue included “several useful, curious and interesting original pieces both in prose and verse, embellished with an exact plan of General Gage’s lines on a large scale, with a description of the plan, number of cannon, shot, &c.” When it came to disseminating news about the Continental Army facing off against British forces during the first months of the Revolutionary War, the Pennsylvania Magazine supplemented coverage in newspapers.

While Aitken certainly welcomed any accounts of current events in Massachusetts, he aimed to compile an array of “useful, curious and interesting” content for his readers. To that end, he proclaimed that he “would be very glad to have some more good original pieces handed to him.” During his time as publisher of the Royal American America, Thomas similarly ran advertisements seeking submissions. He solicited “LUCUBRATIONS,” requesting that “Gentlemen” send them “with all speed to his Printing office.” Aitken did not make his request solely of men, perhaps recognizing that genteel women participated in belles lettres literary circles as both readers and writers. Women used pseudonyms, often classical allusions, in those circles. They could do the same when sending pieces for the magazine. “The exercise of different gifts or talents,” Aitken declared, “add much to the spirit of a Magazine.” Like Thomas, he engaged in an eighteenth-century version of crowdsourcing to generate content for his magazine.