Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

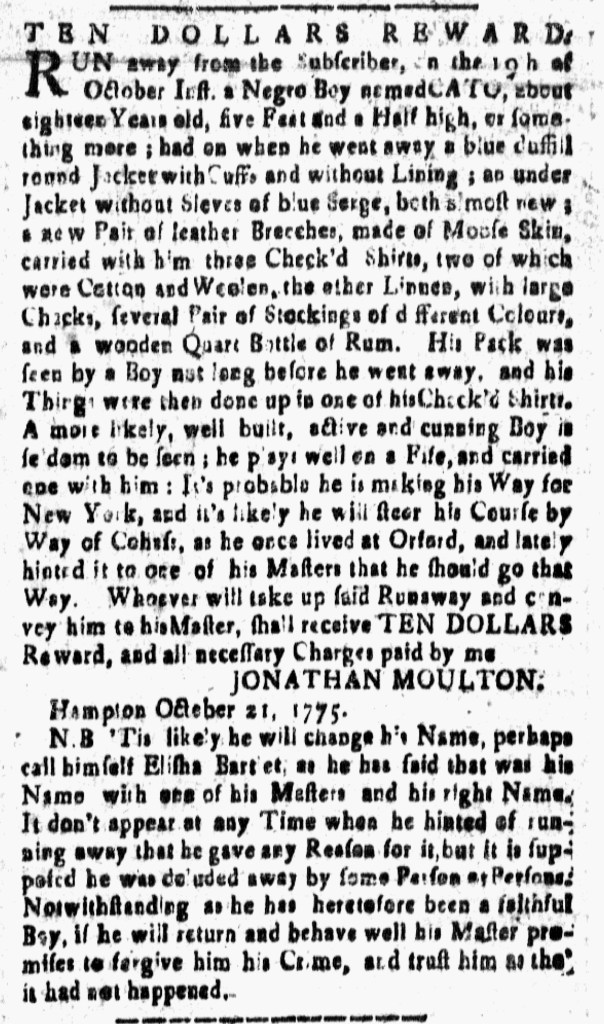

“’Tis likely he will change his Name, perhaps call himself Elisha Bartlet, as he has said that was … his right Name.”

Even though the disruption in the paper supply once again meant that the New-Hampshire Gazette consisted of only two pages instead of the usual four, Daniel Fowle, the printer, found space to publish three advertisements about enslaved men who liberated themselves by running away from their enslavers in the November 2, 1775, edition. They appeared one after the other in the final column on the first page. All three men – Cato (also known as Elisha Bartlet), Peter Long, and Oliver – made their escape in October, perhaps taking advantage of the turmoil caused by the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord the previous spring and the ongoing siege of Boston.

Jonathan Moulton’s advertisement describing Bartlet was about three times the length of Marifield Berry’s advertisement about Peter Long and Gould French’s advertisement about Oliver. Moulton reported on the clothes that Bartlet wore when he departed, noting that he “carried with him three Check’d Shirts [and] several Pair of Stockings of different Colours.” Apparently, Bartlet had been spotted by a boy who observed that “his Things were then done up in one of Check’d Shirts” as a pack that he carried. Moulton suspected that the man he called Cato would “change his Name, perhaps call himself Elisha Bartlet, as he has said that was his Name with one of his Masters and his right Name.” Although not his intention in placing the advertisement, Moulton revealed Bartlet’s commitment to self-determination in naming himself. It did not matter to Bartlet what Moulton or any other enslaver called him at their own whim. He considered Elisha Bartlet his true name, though Moulton did not share enough of the enslaved man’s story to explain why that was the case.

The enslaver did indicate that Bartlet had suggested on more than one occasion that he planned to escape. He thought it “probable [Bartlet] is making his Way for New York,” having “lately hinted it to one of his Masters.” In addition, Moulton stated, “It don’t appear at any Time when he hinted of running away that he gave any Reason for it.” Given the circumstances, Moulton conjectured that Bartlet had been “deluded away by some Person or Persons.” The enslaver seemingly did not entertain the notion that the man he insisted on calling Cato had the same aspirations for freedom that animated so much of the news and editorials about current events that ran alongside his advertisement in the New-Hampshire Gazette. Instead, Moulton asserted that since Bartlet “has heretofore been a faithful Boy, if he will return and behave well his Master promises to forgive him his Crime, and trust him as tho’ it had not happened.” Considering that Bartlet planned his escape from slavery for some time and chose an opportune moment to flee, he likely had little interest in any promises that his enslaver published in the public prints.

[…] December 5, 1775, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette consisted of only two pages rather than the usual four. That limited the amount of news and advertising that the printer, […]