What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Next door but one to the London coffee-house, on Fell’s-Point, Baltimore.”

Baltimore was growing in importance on the eve of the American Revolution, though the port did not yet rival or surpass Annapolis. In August 1773, William Goddard launched the Maryland Journal, the first newspaper printed in Baltimore. Joseph Rathell attempted to establish a circulating library in the fall of 1773, but in the end could not compete with bookseller William Aikman’s library in Annapolis. Still, the advertisements in the Maryland Journal testified to other amenities available in Baltimore, a town that offered a style of life becoming increasingly sophisticated.

Among the advertisements in the May 28, 1774, edition, one promoted a “Stage … between the city of Philadelphia and Baltimore-Town.” Instead of directing their attention solely toward Annapolis, residents of Baltimore also cultivated connections with Philadelphia, the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the colonies. In addition to transporting passengers, the operators of the “stage wagon” and “stage boat” also carried goods. Yet consumers in Baltimore did not need to rely on placing orders with merchants and shopkeepers in Philadelphia or any other city. Retailers in their own town carried all sorts of imported goods. Christopher Johnson and Company advertised their “neat and general assortment of goods, just imported … from LONDON,” listing an array of textiles and housewares comparable to the selection available in towns of all sizes throughout the colonies. In his advertisement, William O’Bryan previewed a “fresh supply of Books, of the latest Publication, from London, Dublin, and Edinburgh.”

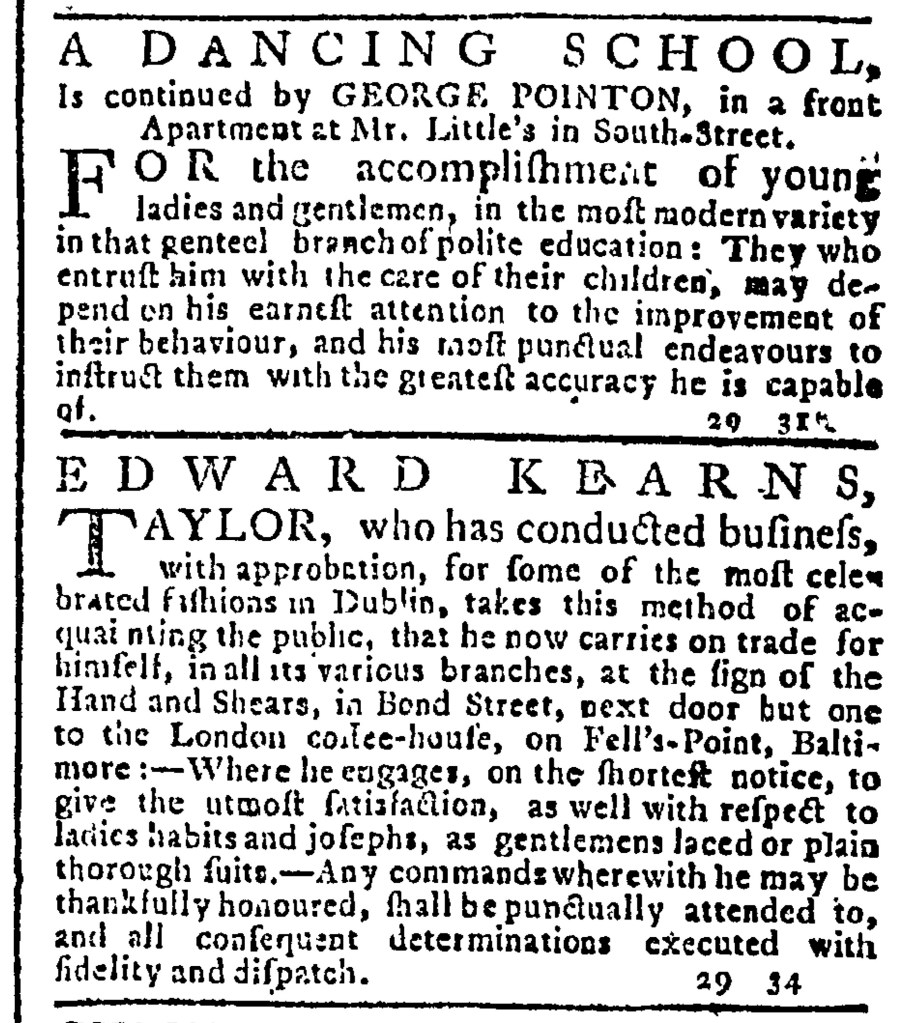

Yet it was not solely the availability of goods that marked Baltimore’s participation in the transatlantic consumer revolution. Residents also appreciated the latest fashions, aiming to demonstrate that even at a distance they kept up with current styles. Edward Kearns, a tailor, trumpeted that he “has conducted business, with approbation, for some of the most celebrated fashions in Dublin.” Clients could find his shop “at the sign of the Hand and Shears, … next door but one to the London coffee-house.” That establishment also represented connections to the metropolis that elevated Baltimore’s standing as more than a distant outpost. In addition, George Pointon ran a “DANCING SCHOOL … FOR the accomplishment of young ladies and gentlemen, in the most modern variety in that genteel branch of polite education.” The dancing master also tended to the comportment of his pupils, pledging “his earnest attention to the improvement of their behaviour.” His description of his services corresponded with newspaper notices placed by dancing masters in major urban ports like Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston. Displays of gentility mattered as much to colonizers in Baltimore as in other cities and towns. Not only did they acquire clothing and goods that matched the latest fashions, they also developed manners that confirmed their status … or at least had opportunities to do so, according to the goods and services represented among the advertisements in the Maryland Journal.