What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“FRENCH SCHOOL.”

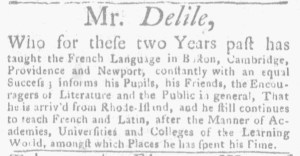

In late February 1774, Mr. Delile, a French tutor, returned to the pages of Boston’s newspapers to alert readers that he had returned to the area and “continues to teach French and Latin.” In an advertisement in the February 24 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter, he reminded residents that “for these two Years past [he] has taught the French language in Boston, Cambridge, Providence and Newport.” He had previously taken to the public prints in two colonies to keep current and prospective pupils advised to his whereabouts, explaining to students in Massachusetts, some of them presumably enrolled at Harvard College, that the “Present Vacation at Cambridge” meant “he can be absent without an Injury to his Pupils.” He pledged to return to the area to guide them in their studies. His new advertisement underscored his previous affiliation with Harvard students and his desire to once again teach them and their peers. He declared that he provided lessons “after the Manner of Academies, Universities and Colleges of the Learning World, amongst which Places he has spent his Time.” Delile offered a proper curriculum, drawing on his own experience and familiarity with educational institutions of the era.

A week after Delile’s notice appeared, Francis Vandale published his own advertisement for a “FRENCH SCHOOL” in the March 3 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter. Although they competed for some of the same clients, Vandale took a different approach than Delile. Rather than targeting young men studying at Harvard, Vandale sought “Gentlemen or Ladies” as pupils. Instead of promoting his method of instruction, he emphasized the genteel qualities of the French language and the social standing his students could achieve under his direction. He conjured an image of how “the French Language when taught agreeable to its native Purity & Elegance, is acquired with that becoming Ease and Gracefulness, as renders it truly Ornamental.” His pupils, through the “Ease and Gracefulness” that Vandale’s tutelage instilled in them, took on the qualities of the language itself. He did not mention any prior affiliations with academies or colleges, instead “profess[ing] to be a compleat Master of [French] in all its original Beauty and Propriety, entirely free from any false Mixture or bad Pronunciation.” For Vandale, speaking French was not an academic exercise but rather a means of artistic expression.

Residents of Boston, Cambridge, and nearby towns who wished to learn or improve their French encountered more than one option when they perused the pages of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter. They could take into account both the reputations and methods of Delile and Vandale when deciding if they wished to hire the services of either French tutor.