What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

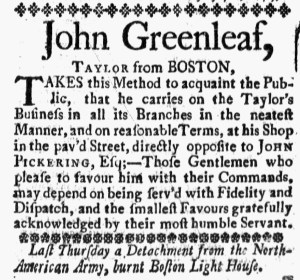

“John Greenleaf, TAYLOR from BOSTON.”

Even though Daniel Fowle sometimes had to reduce the size of the New-Hampshire Gazette to two pages instead of four in the months following the battles at Lexington and Concord, he found space to include advertisements alongside the news of the momentous events taking place in Massachusetts where the siege of Boston continued and General George Washington took command of the Continental Army, in Philadelphia where the Second Continental Congress met to address the crisis, and throughout the colonies as everyone took stock of what occurred and made preparations for what they believed might come next. The July 25, 1775, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette, for instance, consisted of six columns spread over two pages. Several advertisements filled just over half of the final column.

Those advertisements included one from John Greenleaf, “TAYLOR from BOSTON,” who wished “to acquaint the Public, that he carries on the Taylor’s Business in all its Branches in the neatest Manner, and on reasonable Terms, at his Shop” in Portsmouth. After rehearsing common appeals about his skill and the quality of his work (“neatest Manner”) and the price (“reasonable Terms”), Greenleaf emphasized the sort of service that customers expected from tailors: “Those Gentlemen who please to favour him with their Commands, may depend on being serv’d with Fidelity and Dispatch, and the smallest Favours gratefully acknowledged.” The tailor’s advertisement followed a familiar formula, one used by members of his trade from New England to Georgia.

Even listing his occupation and the place he formerly lived and worked (“TAYLOR from BOSTON”) as a secondary headline was part of that formula, yet in this instance doing so had new significance. Greenleaf did not merely communicate that he brought his experience from one of the largest urban ports in the colonies to the smaller town of Portsmouth. He also made a statement about how his life had been disrupted when hostilities commenced in April 1775. He took advantage of negotiations between General Thomas Gage, the governor and king’s representative, and the Massachusetts Provincial Congress that allowed Loyalists to enter Boston and Patriots and others to depart. In describing himself as a “TAYLOR from BOSTON,” Greenleaf declared that he was a refugee, one of many who placed advertisements when they settled in new towns. He likely hoped that would influence prospective customers to avail themselves of his services. The scrap of news that Fowle, the printer, inserted immediately below the tailor’s advertisement underscored Greenleaf’s status as a refugee. “Last Thursday,” Fowle reported, “a Detachment from the North-American Army, burnt Boston Light House.” Greenleaf did not need to elaborate on the dangers he escaped and the challenges he faced in establishing his business in a new town. Readers already knew all about it.