What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“No money be expected until the test of proof shall confirm their intrinsic value.”

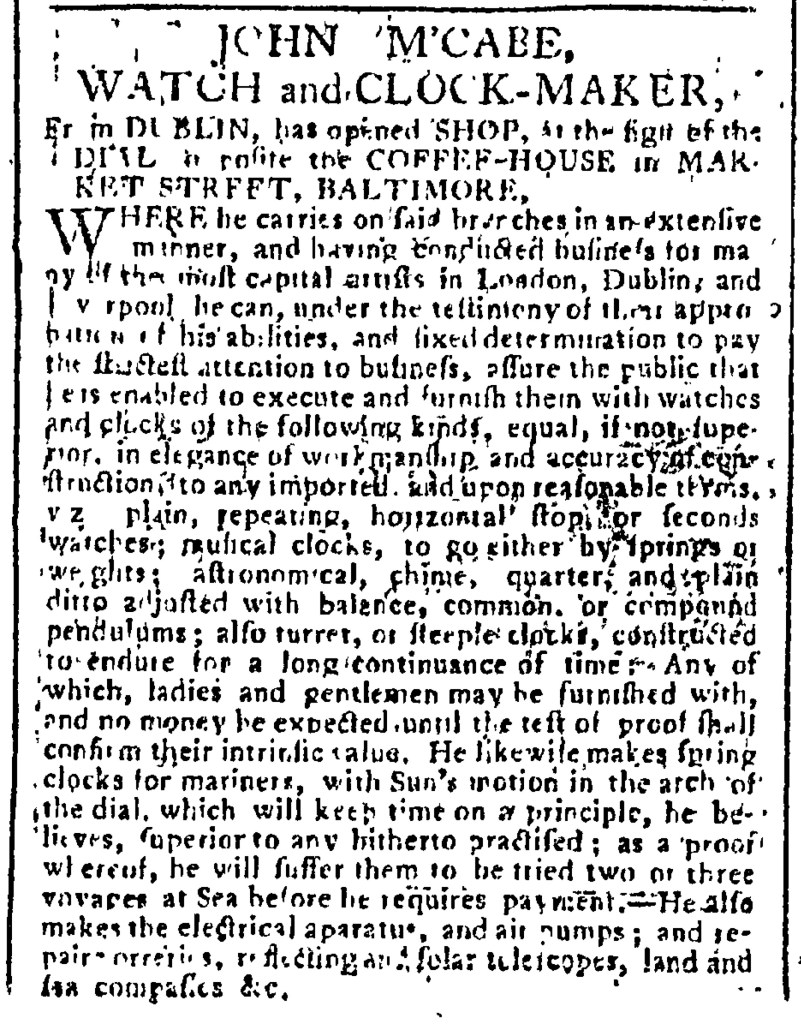

When he set up shop “at the sign of the DIAL” in Baltimore, John McCabe, a “WATCH and CLOCK-MAKER, From DUBLIN,” deployed a marketing strategy commonly undertaken by artisans who migrated across the Atlantic to the colonies. In an advertisement in the June 11, 1774, edition of the Maryland Journal, he sought to establish his reputation in a town that did not have firsthand knowledge of his skill. Instead, he relied on an overview of his experience, asserting that he had “conducted business for many of the most capital artists in London, Dublin, and Liverpool.” Having worked in the most exclusive shops in urban centers, especially the cosmopolitan center of the empire, gave the newcomer a certain cachet, enhanced even more by the “testimony of their approbation of his abilities” that he claimed he could produce.

Yet McCabe did not rest on such laurels that were not immediately apparent to readers. Instead, he simultaneously declared that his “fixed determination to pay the strictest attention to business.” Underscoring his industriousness also came from the playbook developed by other artisans, a familiar refrain in their advertisements. Prospective customers who might have been skeptical of McCabe’s credentials could judge for themselves whether he made clocks and watches “equal, if not superior, in elegance of workmanship and accuracy of construction to any imported.” They could acquire such timepieces “upon reasonable terms,” getting the same style and quality as watches and clocks from London without paying exorbitant prices.

Even though the initial portions of his advertisement resembled notices placed by other artisans, McCabe, he did include an offer not made nearly as often: allowing a trial period for customers to decide if they wished to purchase or return watches and clocks from his shop. The enterprising artisan declared that “ladies and gentlemen may be furnished” with any of the variety of clocks and watches listed in his advertisement and “no money be expected until the test of proof shall confirm their intrinsic value.” McCabe did not explicitly state that customers could return items they found lacking, so confident was he that they would indeed be satisfied with his wares during the trial. He extended a similar offer for “spring clocks for mariners … which keep time on a principle, he believes, superior to any hitherto practised.” Customers could make that determination for themselves: “he will suffer them to be tried two or three voyages at Sea before he requires payment.” Such arrangements would have required some negotiation about the amount of time and the length of those voyages, but allowing for such trials before collecting money from customers did not put McCabe at a disadvantage in the eighteenth-century commercial culture of extending extensive credit to consumers. Prospective customers likely expected credit, so McCabe gained by transforming the time that would elapse between purchase and payment into a trial, giving those customers the impression that they received an additional benefit from doing business with him. For some, that may have been the more effective marketing strategy than any claims about his experience working in the best shops in London, Dublin, and Liverpool.