What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“THE FLYING MACHINE.”

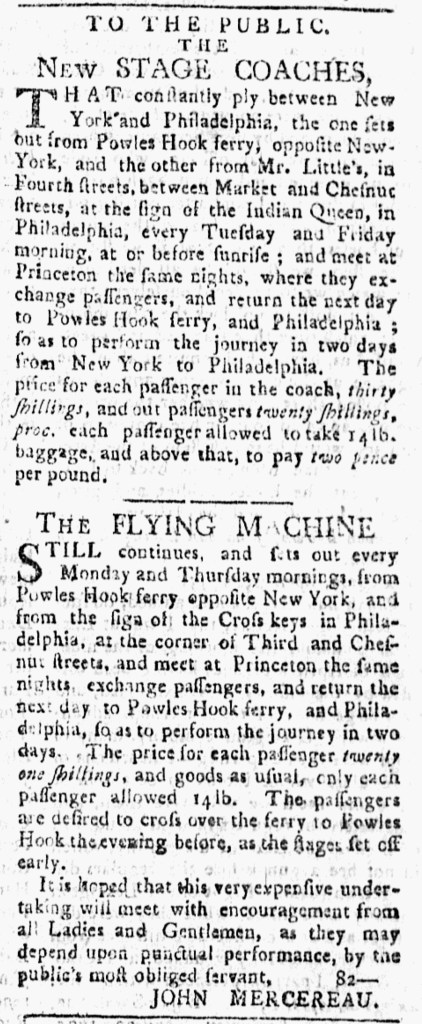

When it came to stagecoaches that connected New and York and Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution, travelers had more than one option. One line, the “NEW STAGE COACHES,” left the Powles Hook ferry, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River “opposite New-York,” and “the sign of the Indian Queen” in Philadelphia on Tuesday and Friday mornings at sunrise. They met at Princeton in the evening, exchanged passengers, and returned to their respective points of departure the next day. Another line, the “FLYING MACHINE,” followed a similar route, one stagecoach leaving from Powles Hook ferry and the other from the “sign of the Cross keys” in Philadelphia. They also met in Princeton, exchanged passengers, and completed the journey in two days. That did not, however, include crossing the Hudson River. John Mercereau instructed passengers departing from New York that they should “cross over the ferry to Powles Hook the evening before, as the stages set off early.” With coaches departing from each city four mornings each week, customers could choose which line best fit their schedules.

Not unlike passengers traveling by bus, train, or airplane today, stagecoach customers considered the prices of each service. The New Stage cost thirty shillings “for each passenger in the coach,” but “out passengers” paid a bargain rate of only twenty shillings. Each had to decide if the comfort of an inside seat was worth the additional cost and fit their budget. The weather on the day of travel likely influenced the choices made by some travelers. The Flying Machine charged twenty-one shillings per passenger, presumably for inside seats. That made it a good deal compared to the New Stage for those who traveled with little luggage. Each passenger was allowed up to fourteen pounds, with no mention of arrangements for anything in excess. The New Stage, on the other hand, allowed fourteen pounds of baggage as part of the fare and then charged two pence per pound for anything above that. Like passengers checking luggage at airports today, travelers apparently went through a process of having their bags weighed and potentially assessed additional fees prior to departure. Those taking more than the allotted amount may have opted for the New Stage over the Flying Machine, resigned to paying more for the excess weight. Like marketing for modern travel that highlights on-time rates, Mercereau promised “punctual performance.” The mode for getting from one place to another has evolved over time, but the many of the considerations that passengers take into account have remained quite similar.