Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“SAMUEL PENNOCK … has thought fit … to publish me in the Pennsylvania Gazette.”

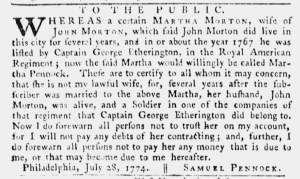

Martha Pennock was not having it. Her husband, Samuel, a hatter, ran a newspaper advertisement that claimed she was not legally his wife because she had previously been married to John Morton of the Royal American Regiment. Her first husband was still alive for several years after Samuel married Martha, making her a bigamist and invalidating her marriage to the hatter. That being the case, Samuel advised the public “not to trust her on my account, for I will not pay any debts of her contracting.” It was quite a twist on the usual “runaway wife” advertisements that appeared so frequently in colonial newspapers.

In another twist, Martha responded in the public prints. Most women did not have the resources to counter the claims made by their husbands, especially after being cut off from their credit. That meant that the public had access to only one account, the one from the husband’s perspective, in newspapers, though conversations and gossip likely circulated alternate versions of what occurred. Martha not only published her rejoinder but did so very quickly. Samuel inserted his advertisement in the August 3, 1774, edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Martha’s notice ran in the next issue on August 10. If she became aware of what Samuel had done quickly enough, she could have responded in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet on August 8, but waiting two more days meant that she presented her side of the story to readers in the same publication that carried her husband’s diatribe against her.

Martha’s narrative was quite different. She blamed the discord on “the instigation of his malicious friends,” asserting that Samuel and his friends “have used me extremely ill, at sundry times.” She denied “with a safe conscience” that she had another living husband, stating that she had been married to Samuel for eight years and “always behaved as a prudent wife to him. If necessary, she could provide “a sufficient testimonial of my lawful marriage to the said Pennock” as well as “an authentic power of attorney, under hand and seal, to collect his debts, and enjoy all that is or may be belonging to him hereafter.” Martha aimed to invalidate any claims that Samuel made, whether about having a first husband or about her rights as Samuel’s “lawful” wife. In doing so, she joined the ranks of relatively few women who responded in print to husbands who used advertisements to disavow their wives and blame them for discord within their households.