What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“WAS committed … a man, by the name of John Smith, being described in the Gazette as a runaway servant.”

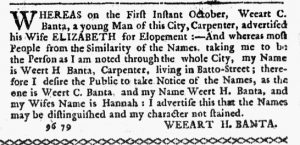

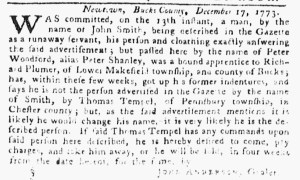

John Anderson, the jailer in Newtown in Bucks County, placed an advertisement in the December 22, 1773, edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette in hopes that it would come to the attention of Thomas Tempel of Pennsbury Township in Chester County, though he likely desired that other readers might supply additional information to help him sort out a situation at his jail. Anderson reported that on December 13 he detained a man named John Smith,” being described in the Gazette as a runaway servant, his person and cloathing exactly answering the said advertisement.” At least some colonizers closely read newspaper advertisements that described runaway indentured servants, convict servants, and apprentices or enslaved people who liberated themselves, making it worth the investment for masters and enslavers to place those notices.

Anderson stated that the man he believed was Smith “passed [in Newtown] by the name of Peter Woodford, alias Peter Shanley” and produced “former indentures” when he claimed he had been “a bound apprentice to Richard Plumer” in Lower Makefield Township in Bucks County. The jailer doubted this story and even the documents that Smith presented because the advertisement that previously ran in the Pennsylvania Gazette “mentions it is likely he would change his name.” Runaway servants and others often utilized that strategy to increase their chances of making good on their escapes. Accordingly, Anderson considered it “very likely he is the described person.” He did not mention any efforts to contact Plumer to determine whether the alleged Smith was actually his former apprentice. Instead, he advised that if Temple “has any commands upon the said person here described” that he should “come, pay charges, and take him away.” Otherwise, Anderson would sell Smith (or whoever he was) into a new indenture “in four weeks,” apparently unconvinced by his insistence that he was Peter Woodford or the documents he carried. A man of low status, unknown to the jailer in Newtown, did not seem to have much recourse to avoid this fate, though perhaps someone that Anderson considered trustworthy would see the advertisement and intervene on the detained man’s behalf. The prisoner also faced the possibility that Tempel would indeed go the Newtown and positively identify him. The power of the press had the potential to negate or, perhaps more likely in this instance, to strengthen the authority exercised by the jailer.