What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A GENTEEL ORDINARY [and] a COFFEE-ROOM.”

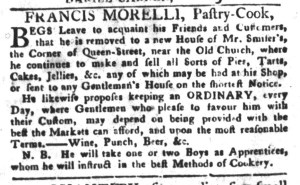

Just six months after advertising that he moved to a new location, Francisco Morrelli (sometimes Francis Morelli), “PASTRY-COOK,” took to the public prints once again to alert “those Gentlemen who were so kind to favour him with their Custom,” along with prospective new customers, that he had moved to a “large and commodious HOUSE” at the corner of Church and Elliott Streets in Charleston. He invited “Gentlemen only” to enjoy “the best Entertainment this Province can possibly afford.” With that invitation, Morelli established his “GENTEEL ORDINARY” as a homosocial space, like many taverns and coffeehouses, for men to gather to eat, drink, conduct business, socialize, discuss politics, conduct business, and gossip. In asserting that “Gentlemen only may be accommodated” at his ordinary, may have also signaled that he welcomed only the better sorts. Others should congregate elsewhere.

Morelli also promoted new services. In his previous advertisement, he invited patrons to imbibe “Wine, Punch, [and] Beer” at his ordinary, while this “large and commodious HOUSE” had space for a “COFFEE-ROOM for the Reception of those Gentlemen who may chuse to drink Tea or Coffee” and “read Papers.” He reported that he “intends to be furnished with every News Paper that can be procured.” That meant local publications, perhaps all three of the newspapers printed in Charleston at the time, as well as newspapers from other cities and towns, especially major ports like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Eighteenth-century coffeehouses often subscribed to newspapers as a service to a clientele that perused them to keep informed about both politics and commerce. The shipping news and prices current from places near and far, for instance, aided merchants in transacting business.

The pastry cook also delivered takeout meals to prospective customers, a service not limited to “Gentlemen only.” Morelli declared that “any Family wanting Dinners or Suppers drest [or prepared] and sent Home to their Houses, may be genteelly served on the shortest Notice.” Other entrepreneurs provided similar services in early America. For instance, when Edward Bardin opened a “compleat Victualing-House” in New York in June 1770, he offered meals “ready dressed, sold out in any Quantity, to such Persons who may find it convenient to send for it.” Meal delivery in American cities dates back at least as far as the eighteenth century.

Morelli concluded his advertisement with a short note about “PASTRY and DESERTS as usual,” hawking the “Pies, Tarts, Cakes, Jellies,” and other treats that he mentioned in an earlier advertisement. They accounted for only a portion of the services and amenities that he presented to current and prospective customers. In addition to selling and delivering meals and pastries, Morelli hoped to make his “GENTEEL ORDINARY” and “COFFEE-ROOM” a destination for merchants, planters, and other local gentry.