Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Alexander Bell, who answers in every respect … the description given of Joseph Anderson.”

Thomas Ennalls offered a reward for the capture and return of “an Irish servant man” who ran away from him in Dorchester County, Maryland, at the end of November 1773. In an advertisement that first ran in the December 16 edition of the Maryland Gazette, Ennalls described Joseph Anderson’s age, appearance, clothing. The runaway, “about thirty years of age,” had “a thin visage” and “wears his own hair tied behind” his head. His apparel included “an old surtout coat, … a knit pattern jacket …, old leather breaches, a pair of ribbed worsted stockings, [and an] English hat cut in the fashion.” Anderson worked as a schoolmaster, but that position of trust did not prevent him from stealing “about eighteen or twenty pounds in cash” when he broke his indenture contract and ran away. Ennalls suspected that the unscrupulous schoolmaster “may change his name.”

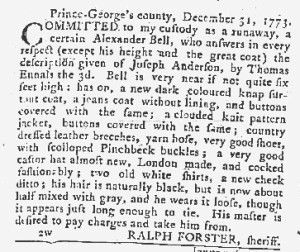

Ralph Forster, the sheriff in Prince George’s County, carefully followed advertisements about runaway indentured servants, convict servants, and apprentices that appeared in the Maryland Gazette. He also placed notices about suspected runaways that he detained. In an advertisement that first appeared in the January 13, 1774, edition of the Maryland Gazette, he described “a certain Alexander Bell, who answers in every respect (except his height and the great coat) the description given of Joseph Anderson, by Thomas Ennals.” Bell was “very near if not quite six feet high,” slightly taller than Anderson’s “five feet nine or ten inches high.” If he was indeed Anderson, he had changed his name as Ennalls anticipated and may have sold, traded, or discarded the coat. The rest of the clothing indeed matched, including “a clouded knit pattern jacket, … country dressed leather breeches, yarn hose, [and] a very good castor hat almost new, London made, and cocked fashionably.” Forster’s requested that his prisoner’s “master … pay charges and take him.”

Among the many purposes served by advertisements in eighteenth-century newspapers, colonizers used them as an infrastructure for surveillance and enforcement in their efforts to maintain order when indentured servants, convict servants, and apprentices ran away from their masters. They served a similar purpose for capturing enslaved people who liberated themselves and returning them to their enslavers. Printers enhanced the power and authority already exercised by colonizers like Ennalls and Forster when they sold them space in their newspapers.