What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“At the Sign of the SCYTHE and SICKLE.”

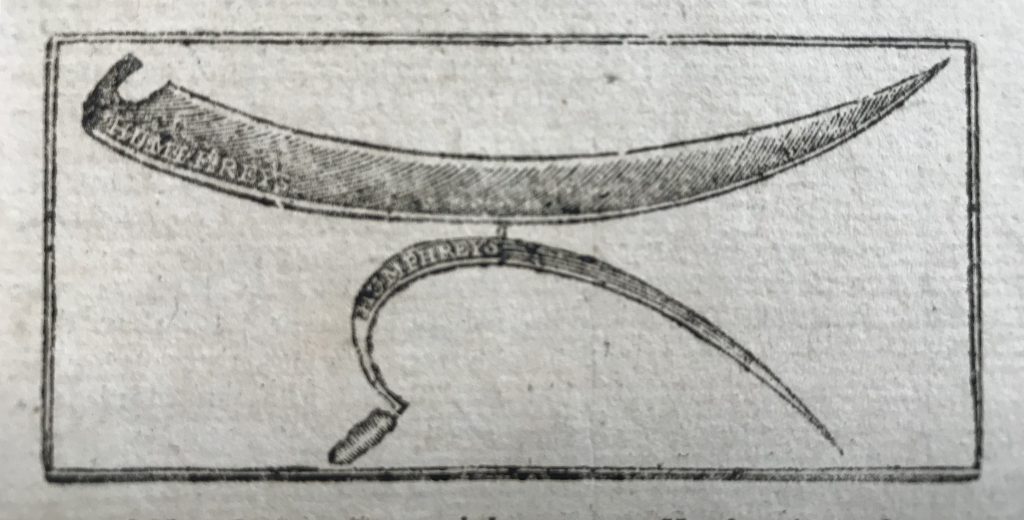

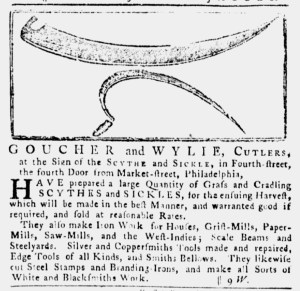

For marking the location of their workshop and for adorning their newspaper advertisements, Goucher and Wylie, cutlers, used an image closely associated with their trade. In an advertisement that ran in the Pennsylvania Gazette for several weeks in the spring and summer of 1774, they advised prospective customers that they made and sold all kinds of cutlery “at the Sign of the SCYTHE and SICKLE.” The woodcut that accompanied their notice depicted a scythe and a sickle within a rectangular border, perhaps replicating their shop sign or perhaps merely evoking the same symbols. Either way, the image made their advertisement more visible to readers while simultaneously prompting them to think of Goucher and Wylie when they glimpsed scythes and sickles.

Yet they were not the only cutlers to operate at the Sign of the Scythe and Sickle in Philadelphia in the early 1770s. Stephen Paschall and his son, also named Stephen, previously ran advertisements that gave their location as “the Sign of the Scythe and Sickle, in Market-street, between Fourth and Fifth-streets,” the most recent appearing a year before Goucher and Wylie published their notice. In the longer version of their location, Goucher and Wylie directed customers to “the Sign of the SCYTHE and SICKLE, in Fourth-street, the fourth Door from Market-street.” In other words, Goucher and Wylie were just around the corner from the Paschalls. Did both businesses use the same device in such close proximity? Or had the Paschalls closed shop, leaving the Sign of the Scythe and Sickle up for grabs for any cutlers who wished to appropriate it (and perhaps benefit from the reputation already associated with that image)? Alternately, the Paschalls might have transferred the Sign of the Scythe and Sickle to Goucher and Wylie.

Let’s examine the evidence for that last possibility. In June 1770, Samuel Wheeler advertised that he kept shop “at the sign of the Scythe, Sickle and Brand-iron” at the same time that Stephen Paschall ran notices that gave his location as “the sign of the Scythe and Sickle, in Market-street.” Wheeler carefully added an item to his sign to distinguish his business from Paschall’s. Had the elder and younger Paschall still been in business around the corner in 1774, Goucher and Wylie may have hesitated to duplicate their sign and, by extension, the name of their business. In May 1768, Stephen Paschall and Benjamin Humphreys placed a joint advertisement that featured an image of a scythe and sickle enclosed in a rectangular border. Both items bore the name “HUMPHREYS.” That woodcut appears identical to the one in Goucher and Wylie’s advertisement that ran six years later, with the exception of “HUMPHREYS” being removed. Perhaps Paschall had retained the woodcut when his association with Humphreys ended but had not made use of it. He could have passed along the woodcut to Goucher and Wylie when transferring the Sign of the Scythe and Sickle to them. If this scenario did occur, it suggests that some artisans carefully curated the names and images associated with their businesses in colonial Philadelphia.