What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

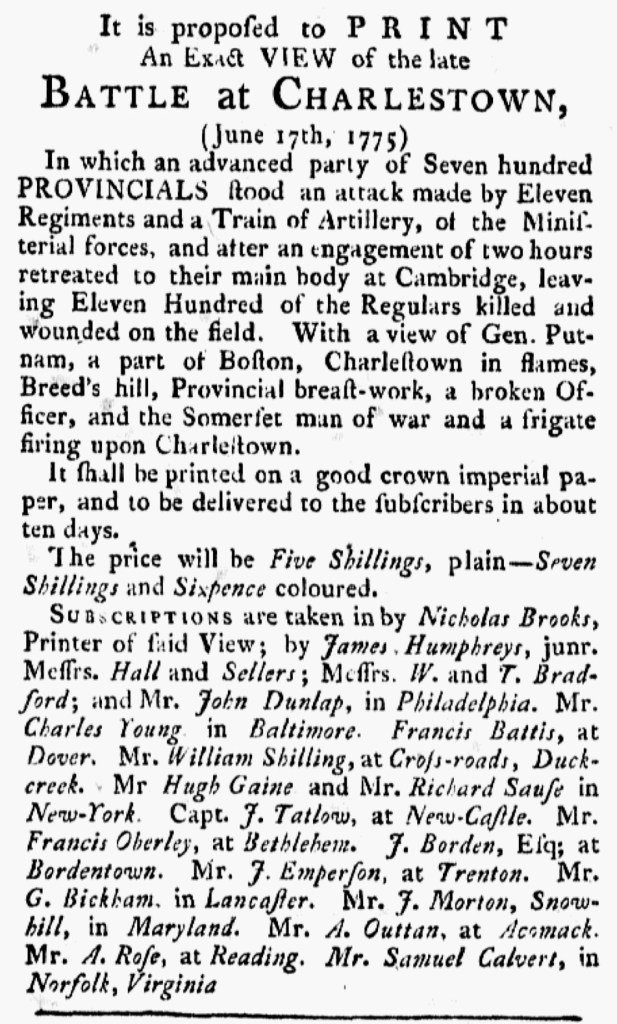

“It is proposed to PRINT An Exact VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN.”

Bernard Romans, a cartographer, apparently met with sufficient success in marketing and publishing his “MAP, FROM BOSTON TO WORCESTER, PROVIDENCE AND SALEM” in the summer of 1775 that he launched a similar project as fall arrived. He placed a subscription proposal for a print depicting “An Exact VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN,” known today as the Battle of Bunker Hill, in the September 16, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger. The proposal stated that it “shall be printed on a good crown imperial paper” at a price of five shillings, “plain,” or seven shilling and six pence, “coloured.”

In promoting the print, Romans summarized the battle, though most readers likely already knew the details. “[A]n advanced party of Seven hundred PROVINCIALS,” the cartographer narrated, “stood an attack made by Eleven Regiments and a Train of Artillery, of the Ministerial forces, and after an engagement of two hours retreated to their main body at Cambridge, leaving Eleven Hundred of the Regulars killed and wounded on the field.” Even though the British prevailed, it was such a costly victory in terms of casualties that officers that British General Henry Clinton wrote in his diary, “A dear bought victory, another such would have ruined us.” The Americans had reason to feel proud despite retreating. Romans hoped to capitalize on that even as he aimed to publish a print that helped colonizers far from Boston visualize the battle. The print included “a view of Gen. [Israel] Putnam,” an American officer, “a part of Boston, Charlestown in flames, Breed’s hill, Provincial breast-work, a broken Officer, and the Somerset man of war and a frigate firing upon Charlestown.”

As had been the case with his map, Romans collaborated with Nicholas Brooks, a shopkeeper and “Printer of said View” as well as local agents in several cities and towns from New York to Virginia. The subscription proposal indicated that the print would be ready “to be delivered to the subscribers in about ten days,” not nearly enough time to disseminate the proposal and collect the names of subscribers before making the first impressions. In both instances, Romans likely felt confident that consumers would be so interested in purchasing items that commemorated the newest chapter in the struggle against Britain that the demand for the map and the print would justify the expense of producing initial copies as well as prompt him to issue even more as local agents submitted their lists of subscribers.