Readers who visit regularly know that I usually post extended commentary about methodological issues on Fridays, but I would like to depart from that today. It has been a while since I featured any marketing materials other than the day’s featured advertisement. When I expanded this project from Twitter to a blog I intended to use the “extra” space available to incorporate posts exploring other aspects of advertising in eighteenth-century America more regularly. After all, my handle on Twitter is @TradeCardCarl, so let’s see some trade cards!

In addition, in the course of my research I have identified more than a dozen forms of printed ephemera that circulated as advertising in eighteenth-century America, including trade cards, magazine wrappers, billheads, furniture labels, catalogues, and broadsides. I would like the Adverts 250 Project to explore all of those, even as it remains faithful to its primary mission, a “new” newspaper advertisement featured every day.

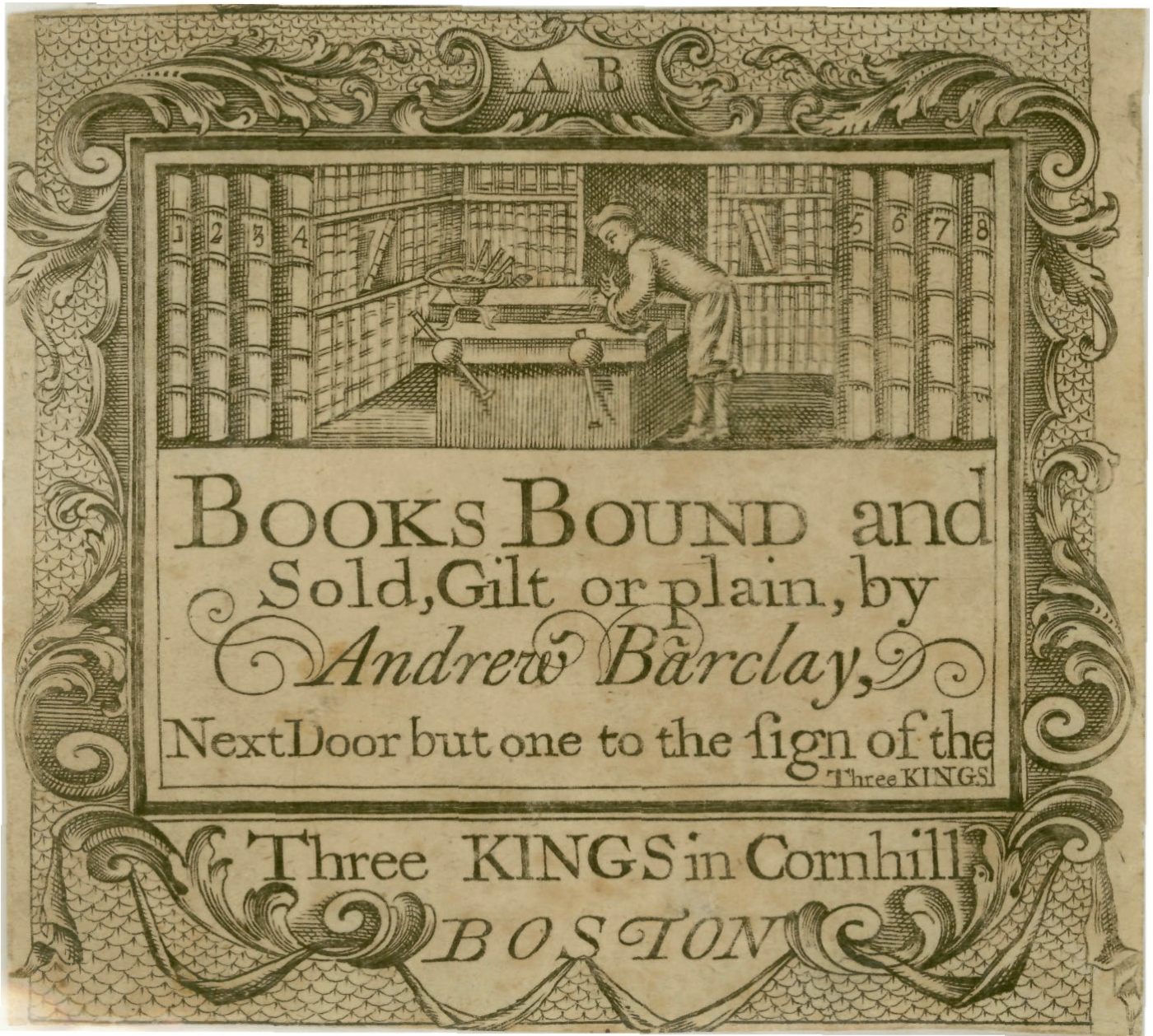

As I include diverse advertising media in the coming weeks and months, much of it will come from decades other than the 1760s. For today, however, I have chosen two items that would have been in circulation at the same time as the newspaper advertisements featured throughout the week: trade cards issued by bookbinder Andrew Barclay in the mid 1760s.

The first, according to the American Antiquarian Society’s catalog, dates to approximately 1764 through 1767. It measures 11 cm x 12 cm (or 4¼ in x 4¾ in).

(Let’s take a little digital humanities detour here. As I have stated repeatedly, digital sources are wonderful and have revolutionized the work done by scholars and opened up new levels of access to historic sources for scholars and general audiences alike. But digital sources are not without their shortcomings. Viewing original sources on screens tends to standardize them. They appear to “be” whatever size the screen happens to be. As a result, all sources take on the same size. Others with much more digital humanities experience have commented on this at great length, but it bears repeating here, especially since I will be returning to the actual size, rather than the virtual size, of today’s featured trade cards later.)

The second, again according to the American Antiquarian Society’s catalog, dates to approximately 1765 through 1767. It measures 6 cm x 9 cm (or 2½ in x 3½ in).

Both trade cards list the same address, but use slightly different language: “Next Door but one to the sign of the Three KINGS … in Cornhill Boston” and “next Door but one North of the three KINGS, in Cornhill Boston.” Thomas Johnston (1708-1767) engraved both. (Johnston’s death explains why both cards have been dated to 1767 at the latest.)

Unlike most of the newspaper advertisements for goods and services printed in the 1760s, these trade cards used both text and images to make appeals to potential customers. In addition to giving Barclay’s location, both announced that he bound and sold books, “Gilt or plain.” Consumers were accustomed to making choices and selecting goods that corresponded to their rank and stature. Offering “Gilt or plain” bindings allowed customers to choose features that corresponded to other decisions they made about how to present themselves to others.

Each trade card included an image of man leaning over a bookbinding press, hard at work. Shelves stocked with books are on display in the background. The books, bookbinding press, and assorted tools were testaments to Barclay’s trade. Both images also suggested an important quality that Barclay wanted past and potential customers to associate with him: industriousness. In both images, a bookbinder wearing an apron could be seen busily at work. Benjamin Franklin did not begin writing his famous Autobiography until 1771 (and it was not published until 1791, after his death), but other eighteenth-century artisans certainly knew the value of industry and the appearance of industriousness that Franklin extolled in his memoir.

Classifying and cataloging early American advertising media is as much art as science. Such items often defy strictly defined categories. I have described both of these items as “trade cards.” In the AAS catalog, however, both are described as “advertising cards” in the genre/form field. That seems like an appropriate description. Although I have heard curators and other staff at the AAS refer to such items as “trade cards,” there are a variety of reasons why catalogers would choose the alternate (and perhaps broader) “advertising cards” to classify these items.

One of these trade cards was featured in The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World, the first volume of the impressive History of the Book in America. There it is described as a “binder’s label.” That is a much narrower category than either “trade card” or “advertising card.” It is likely more accurate for its specificity (but I believe that fewer researchers would find it in the AAS catalog if it were classified only as “binder’s label” rather than “advertising card”).

This is where the size of these items becomes important. Most trade cards were larger, making them easier to pass from hand to hand, but also significant enough that they would not be misplaced easily. Many also tended to be large enough that vendors could record purchases and write receipts on the reverse (transforming them into billheads, of sorts).

These relatively small items, on the other hand, would have much more easily gotten lost in the shuffle or discarded … unless they were secured inside a book. Andrew Barclay likely pasted one of these labels inside some of the books he bound for his patrons. In the process, he transformed both the service he provided and the goods he sold into advertising media. When that happened, colonial consumers did not possess their books exclusively; instead, they shared ownership with an artisan who left his mark on a material object that happened to be in their possession. Some readers pasted their own bookplates in the volumes they owned, but Andrew Barclay’s binder’s label pre-empted that practice. Consumers could still place a bookplate in books bound by Barclay, but unless they pasted their own bookplate over his label, their act of taking possession competed with, rather than negated, Barclay’s label.

In the end, readers who took their books to Barclay to be bound ended up purchasing an advertisement that they would later encounter every time they used the item they had purchased from him. Every time they opened a book bound by Barclay consumers were once again exposed to his binder’s label advertisement.

Great post, Carl!

I’ve really been enjoying reading the selections from your students. It’s a fascinating way to reuse the material with a pedagogical benefit. Your creativity is appreciated.

Elizabeth

Reblogged this on JANINEVEAZUE.

[…] couple of months ago I examined binder’s labels and trade cards, arguing that when they were affixed to books they became paratexts that transformed goods that […]

[…] went into selecting materials and appearance for bindings. In turn, bookbinders inserted their own binder’s labels into books to further advertise their […]

[…] paper labels, which often resembled trade cards, to furniture produced in their shops. Bookbinders pasted labels inside the covers of books they bound. Smiths packaged buckles and other adornments in boxes that […]