GUEST CURATOR: Lindsay Hajjar

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

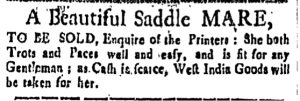

“A Beautiful Saddle MARE”

Owning nice things was a luxury that not every colonist had the opportunity to experience because of their financial situation. This advertisement targeted someone who could afford the extravagance of having a horse that was intended to be an accessory and a marker of status. When the seller described the mare he said,“She Both Trots and Paces well and easy.” This showed that the mare was in good condition, was even tempered, and could be ridden for leisure and pleasure. The mare was probably not meant to be a working house. This seems clear because the seller did not provide her age and weight, whether she had had any colts, or whether she was healthy and fit to work and breed. He described her as “A Beautiful Saddle MARE,” one ready to be shown off.

Conspicuous consumption of this sort suggests a growing sense of individuality among the colonists. As time went on and as their farms and businesses flourished and grew many had the financial stability to purchase goods that they would not have been able to afford had they stayed in Europe. The colonists’ sense of self was starting to shine through more and more as their wealth grew. Many colonists were able to make purchases that reflected their desires rather than just obtaining necessities.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Newspapers advertisements provide revealing glimpses of how the colonial marketplace operated, but sometimes they fall frustratingly short of revealing all the details that would allow us to make sense of the transactions they promoted. Lindsay has selected an advertisement that tells only a portion of a longer story.

An unknown seller sought a buyer for “A Beautiful Saddle MARE,” noting that she was “fit for any Gentleman.” In this case, referring to the purchaser as a “Gentleman” most likely was not a courtesy but rather an indication that the owner of such a horse would be an individual of some stature in the community, somebody with the resources to maintain the mare as a status symbol.

The same was presumably true of the current owner of the “Beautiful Saddle MARE,” yet the advertisement does not reveal the seller’s identity. Instead, it merely stated “Enquire of the Printers.” Who was the seller? Why was the horse offered for sale? Why did the seller conceal his identity?

A dozen different stories and scenarios spring to mind, each of them pure conjecture because the advertisement offers so few clues. In that regard, this advertisement seems ideal for working on a project with students. It demonstrates the historians must work within the limits of the documents available to us. We can work imaginatively but responsibly with our sources. We can make inferences from the language and context, as Lindsay has done in positing that this was not a workhorse intended for labor on a farm. Doing so allowed her to imagine what else could be learned from this advertisement, even if it was not stated explicitly. In the process, she reconstructed the social meanings of colonists’ possessions, extrapolating from the advertisement.

In that regard, Lindsay demonstrates that this advertisement tells us more about colonial society than might have initially seemed apparent. However, some aspects of the advertisement remain out of reach. I was drawn to this advertisement because it indicated that since “Cash is scarce, West India Goods will be taken for her.” What did the seller intend to do with a quantity of “West India Goods” exchanged for “A Beautiful Saddle MARE” that was “fit for any Gentleman?” Would those goods have been put to personal use or would they have been traded or sold to other consumers? That is a story of the colonial marketplace that will remain untold.