What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

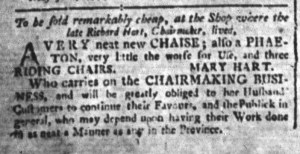

“MARY HART … will be greatly obliged to her Husband’s Customers to continue their Favours.”

When she took to the pages of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette in the summer of 1774, Mary Hart advertised several wheeled vehicles for sale “remarkably cheap, at the Shop where the late Richard Hart, Chairmaker, lived” in Charleston. Her inventory included a “VERY neat new CHAISE,” described by the Oxford English Dictionaryas a “light open carriage for one or two persons, often having a top,” and a “PHAETON, very little the worse for Use,” described as a “light four-wheeled open carriage, usually drawn by a pair of horse, and having one or two seats facing forward.” Like the modern automobile industry, Hart marketed both new and used vehicles. She also had three “RIDING CHAIRS,” which public historians at George Washington’s Mount Vernon describe as a “wooden chair on a cart with two wheels … pulled by single horse.” They explain that riding chairs “could travel country lanes and back roads more easily than bulkier four-wheeled chariots and coaches.” Hart offered different kinds of wheeled vehicles to suit the needs, tastes, and budgets of her customers.

The widow did not merely seek to sell carriages previously produced by her late husband. Instead, she announced that she “carries on the CHAIRMAKING BUSINESS.” Eighteenth-century readers understood that she referred to making wheeled vehicles, not household furniture. Her husband had cultivated a clientele for the family business, one that Hart wished to maintain and even expand. She declared that she “will be greatly obliged to her Husband’s Customers to continue their Favours, and the Publick in general, who may depend upon having their Work done in as neat a Manner as any in the Province.” Did Hart construct carriages herself? Perhaps, though if that was the case it demonstrated what was possible rather than what was probable. In a dissertation on “Women Shopkeepers, Tavernkeepers, and Artisans in Colonial Philadelphia,” Frances May Manges demonstrated that female entrepreneurs worked in a variety of trades.[1] Hart may have worked alongside her husband before his death and then continued. Rather than building carriages, she may have supervised employees in the workshop, running other aspects of the business both before and after her husband’s passing. Either way, she confidently asserted that a workshop headed by a woman produced carriages equal in quality to any others made in the colony. Out of necessity, Hart joined the ranks of widows who continued operating family businesses in colonial America.

**********

[1] Frances May Manges, “Women Shopkeepers, Tavernkeepers, and Artisans in Colonia Philadelphia” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1958).