What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“THEIR WHITE and COLOURED PLAINS, which coming, as usual, from the first Hands, the quality will recommend itself.”

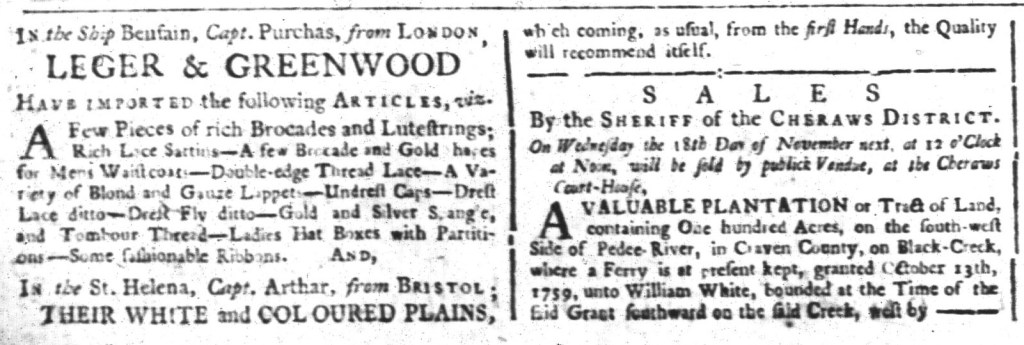

Robert Wells, the printer of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, may have experienced a disruption in his paper supply in October 1772. That would explain the unusual format of the October 5 edition. The newspaper usually featured four columns per page. The October 5 edition did indeed have four columns on each page, but one of those columns was narrower than the other three. In order to reuse advertisements with type already set, Wells rotated the text ninety degrees to fill the fourth column with six short columns that ran perpendicular to the rest of the text. In the past, he had sometimes adopted this strategy when forced to use paper of a different size than usual. Wells usually selected short advertisements and left them intact. In contrast, this time he used advertisements that overflowed from one column to another in the October 5 edition.

Whether Wells was forced to do so remains a mystery, due in part to working with digitized images of the newspaper rather than original documents. Digitized images do not have any particular dimensions. They fit the size of the screen of the viewer. They can be magnified to see details betters. They do not have a fixed size the reader can measure. As a result, I cannot measure pages of the September 28 and October 5 editions to compare them. An inspection of one visual aspect further suggests that Wells used a slightly smaller sheet on October 5. There does not appear to be as much space between the title of the newspaper and the page number running across the top on pages from October 5 compared to pages from September 28.

Those page numbers introduce another uncertainty into figuring out why Wells might have decided to distribute an edition with an unusual format. The September 28 edition concluded with page 244. The available pages for the October 5 edition commence with page 249. It does not have the standard masthead. This was not a numbering error. Page 249 includes “EUROPEAN INTELLIGENCE. (Continued from Page 246.)” The four pages with a narrow column of perpendicular text were likely an insert that accompanied the standard issue for the week. Did Wells use the usual size sheet for the standard issue and then a slightly smaller size for the insert? Printers sometimes did so with significantly smaller sheets when they did not have sufficient content to fill pages of the usual size, but these pages were not significantly smaller. Rotating the type and breaking advertisements that previously appeared in a single column into shorter segments that ran in multiple columns seems like unnecessary labor when Wells could have instead inserted more “EUROPEAN INTELLEIGENCE” or “AMERICAN INTELLIGENCE” or even inserted an advertisement from a previous edition gratis to fill the space.

The combination of the missing pages and working with digital surrogates make it difficult to know for certain why Wells adopted an unusual format for the October 5 edition of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette. Did that format work to the advantage of advertisers? Did it draw attention to the items in the column set perpendicular to the rest of the page? Readers may indeed have been curious to discover what kind of content ran along the edges.