What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Excellent Tea.”

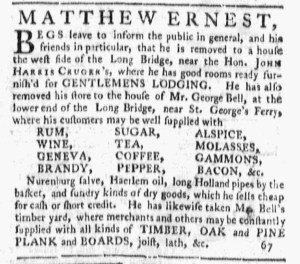

Despite the complicated politics of tea in the wake of the Boston Tea Party and the Boston Port Act that closed and blockaded the harbor as punishment, some merchants and shopkeepers continued to sell tea and printers continued to publish their advertisements in the summer of 1774. At the same time that many advertisers quietly dropped tea from the lists of merchandise in their newspaper notices, others refused to do so. In New York, for instance, Matthew Ernest enumerated a dozen commodities that customers could acquire at his store. In capital letters in three columns, making each item easy for readers to spot, Ernest listed “RUM, WINE, GENEVA, BRANDY, SUGAR, TEA, COFFEE, PEPPER, ALSPICE, MOLASSES, GAMMONS, [and] BACON.” The merchant supplied tea to consumers willing to purchase it.

One printer, James Rivington, even sold tea himself or acted as a broker for a customer who did wish for their name to appear in print. For many weeks, Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer ran an advertisement that announced “Excellent Tea” in a font much larger than almost anything else that appeared among news or advertisements. It further clarified, “SUPERFINE HYSON, To be sold. Enquire of the Printer.” Colonial printers often stocked books, stationery, patent medicines, and other goods, so perhaps Rivington sought to supplement revenues with tea. On the other hand, an advertisement on the same page as the “Excellent Tea” notice in the July 28 edition promoted “Middleton’s incomparible Pencils, Red and black Lead, Sold by James Rivington.” Whether or not he was the purveyor of the tea or merely a broker, the printer disseminated the advertisement and sought to earn money through trucking in tea.

In Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776, James R. Fichter argues that most colonizers who continued to advertise tea did not face significant repercussions, quite a different interpretation than the traditional narrative. “If we only look at people who got in trouble over tea,” Fichter states, “we will think tea was troublesome. But if we note the hundreds of people who did not get in trouble over tea, we see a very different story.”[1] Even as the imperial crisis intensified, there was still space in the public marketplace for advertising and selling tea in the summer of 1774.

**********

[1] James R. Fichter, Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2023), 145.