Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Several very valuable FAMILY SERVANTS.”

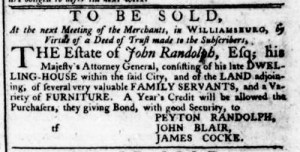

A notice concerning the “Estate of John Randolph, Esq; his Majesty’s Attorney General,” first appeared in the October 14, 1775, edition of John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette. It was not Randolph’s death that occasioned the notice. Instead, the Loyalist and his family departed for England at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, leaving trustees in charge of selling “his late DWELLING-HOUSE” in Williamsburg, “several very valuable FAMILY SERVANTS, and a Variety of FURNITURE.”

At a glance, modern readers might assume that those “FAMILY SERVANTS” consisted of indentured servants like the ones that had “JUST ARRIVED” in Virginia on the Saltspring. According to an advertisement on the next page, those servants included “many Tradesmen,” such as carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, weavers, a cabinetmaker, and a wheelwright, as well as “FARMERS and other COUNTRY LABOURERS.” Yet that almost certainly was not the case for the “FAMILY SERVANTS” in the notice about Randolph’s estate. They did indeed possess a variety of skills like the indentured servants recently arrived in the colony, yet that phrase – “FAMILY SERVANTS” – referred to enslaved people who had been part of the Randolph household.

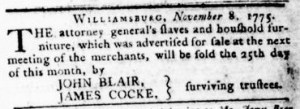

A subsequent advertisement did not use the same turn of phrase. After Peyton Randolph, one of the trustees, died suddenly on October 22, a new advertisement that first appeared in the November 9 edition of John Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette clarified that the “attorney general’s slaves and household furniture, which was advertised for sale at the next meeting of the merchants, will be sold the 25th day of this month, by JOHN BLAIR, [and] JAMES COCKE, surviving trustees.” Of course, eighteenth-century readers understood the reference to “FAMILY SERVANTS” in the original advertisement. They did not need a subsequent notice to clarify that it meant enslaved men and women. They knew the lexicon of newspaper notices about enslaved people just as well as they knew the lexicon of consumer culture in advertisements that promoted all sorts of goods, especially textiles, with names that seem unfamiliar to today’s readers.

[…] advertisement for the “Estate of John Randolph” that ran in John Dixon and William Hunter’s Vi… in the fall of 1775 also appeared in the other newspapers published in Williamsburg, John […]