What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Provedore to the Sentimentalists will exhibit food for the mind.”

Readers of the November 18, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post encountered two advertisements promoting an “AUCTION of BOOKS,” one placed by Charles Mouse, “auctionier,” and the other by Robert Bell, “bookseller and auctionier.” Mouse operated a “vendue store,” a combination of an auction house and a flea market, where he had a “large and choice collection of the most useful and entertaining [books].” He invited those who had books to sell and “will[ing] to take their chance by auction” to deliver them to his vendue store on Second Street in Philadelphia. The auctions would begin “precisely at six each evening” and “continue till the whole are sold.” Mouse provided a straightforward account of this endeavor.

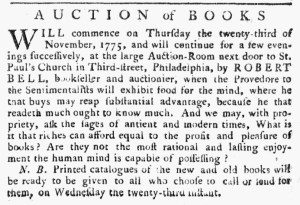

Robert Bell, on the other hand, crafted a more elaborate advertisement. One of the most prominent American booksellers in the second half of the eighteenth century, Bell already established a reputation throughout the colonies by the time he advertised an auction “at the large Auction-Room next door to St. Paul’s Church in Third-street, Philadelphia,” scheduled for November 23. He colorfully referred to himself in the third person as “the Provedore to the Sentimentalists” who would “exhibit food for the mind” to bidders and curious observers. Those who made purchases, Bell declared, “may reap substantial advantage, because he that readeth much ought to know much.” He further mused that “we may, with propriety, ask the sages of antient and modern times, What is it that riches can afford equal to the profit and pleasure of books? Are they not the most rational and lasting enjoyment the human mind is capable of possessing?” Mouse’s description of his “large and choice collection of the most useful and entertaining [books]” paled in comparison to the appeals that Bell made to readers.

Bell deployed another strategy to entice prospective bidders. In a nota bene, he informed them that “[p]rinted catalogues of the new and old books will be ready to be given to all who choose to call or send for them.” Those catalogues gave a preview of the sale and allowed Bell to disseminate information about the books up for bids more widely. Those who visited his “Auction-Room” to collect a catalogue likely had an opportunity to browse the books, yet they could take their time going through the entries in the catalogue in the comfort of their own homes or offices or even at a coffeehouse with friends. Those who sent for catalogues enjoyed the same benefit. By distributing catalogs, Bell encouraged interest and prompted readers to imagine themselves bidding on the books they selected in advance. He may have believed that prospective bidders were more likely to bid higher prices if they had spent time with the catalogue in advance and, as a result, became more committed to acquiring the books that interested them.

[…] The flamboyant Bell was already known as “the Provedore to the Sentimentalists” from his newspaper advertisements, broadsides, and book catalogs. He sought to maintain the image he cultivated by including that […]