What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“50 Stands of FIRE-ARMS, with Bayonets.”

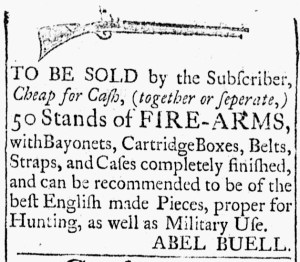

The image distinguished the advertisement from most of the others that ran in the March 4, 1774, edition of the Connecticut Journal. A woodcut depicting a gun adorned Abel Buell’s advertisement for “50 Stands of FIRE-ARMS, with Bayonets, Cartridge Boxes, Belts, Straps, and Cases completely finished.” Only two other images appeared in that issue, a post rider on a horse in the masthead, as usual, and a house in an advertisement in a real estate advertisement. Printers supplied stock images of houses, horses, ships, and enslaved people when they matched the contents of the notices in their newspapers. Advertisers interested in other images, including those that replicated their shop signs or represented their merchandise, commissioned the woodcuts and then had exclusive use of them. In some instances, such advertisers in towns with more than one newspaper sometimes collected their woodcuts from one printing office and delivered them to another when they chose to advertise in multiple publications.

Buell’s woodcut was noteworthy for other reasons. Not especially sophisticated to modern eyes, it was a rarity in the Connecticut Journal. Newspapers in urban ports tended to carry a greater number of images commissioned by advertisers, but Thomas Green and Samuel Green in New Haven did not handle that many special orders. That made Buell’s woodcut all the more innovative and eye-catching in that particular newspaper. In addition, it did not correspond to his trade. In previous advertisements, he described himself as a “GOLDSMITH in New-Haven” and listed a variety of jewelry available at his shop. Yet as spring approached in 1774, he marketed dozens of “the best English made Pieces, proper for Hunting, as well as Military Use.” Buell made an investment in a woodcut unrelated to his primary occupation, though he may have produced it himself rather than commissioning it. His skills included engraving. A decade earlier, according to the Library of Congress, he “used his skill as an engraver to produce counterfeit colonial paper currency, a crime for which he was tried and convicted.” Following that incident, he put his skills to better use, producing “the very first map of the newly independent United States compiled, printed, and published in America by an America.” Perhaps along the way he made a woodcut to enliven his advertisement for firearms in the Connecticut Journal.