What was advertised in a colonial American magazine 250 years ago this month?

“A concise, but just, representation of the hardships and sufferings of the town of BOSTON.”

For eighteen months, the Adverts 250 Project has been tracing the efforts of, first, Isaiah Thomas and, eventually, Joseph Greenleaf in advertising and publishing the Royal American Magazine. Newspaper advertisements have definitively demonstrated that the dates associated with most issues did not match when they were published and distributed to subscribers and other readers. On October 13, 1774, for instance Greenleaf placed advertisements in both the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter and the Massachusetts Spy to announce “This day was published, THE Royal American Magazine, No. 8. For AUGUST, 1774. In the eighteenth century, magazines usually came out at the end of the month, so readers would have expected to see the September issue advertised in October. Greenleaf continued to work on catching up on delinquent issues after acquiring the magazine from Thomas.

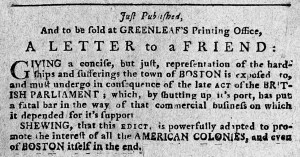

Greenleaf packaged the August issue in wrappers intended to be removed when the subscriber had the monthly issues bound into a single volume. The pages numbers continued from one issue to the next. The wrapper supplemented a title page that included a list of contents within the issue; printers intended for the title page to remain after discarding the wrapper. Unlike modern magazines, advertisements did not appear within the issue. Instead, they ran only on the wrappers. The front of the wrapper for the August 1774 issue of the Royal American Magazine featured the same items as the one for July: the coat of arms of Great Britain above the title of the magazine (along with an updated date and issue number), an address to subscribers from Thomas, and an advertisement for “A LETTER to a FRIEND: GIVING a concise, but just, representation of the hardships and sufferings the town of BOSTON is exposed to” available at Greenleaf’s printing office.

What about the back of the wrapper? That presented a bit of a mystery that cannot be solved solely by examining the digital surrogates. A list of books and blanks that Greenleaf sold filled the back of the wrapper that accompanied the July issue. That was also the case for the September issue. The digitized version of the August issue, however, does not include any trace of the back of the wrapper, not even images of blank pages. It does include an image of the blank page that was the interior of the front of the wrapper with the impression of the title and date from the other side clearly visible. The same database includes images of blank pages for the interiors of front and back wrappers for the July and September issues, demonstrating that production of the digital surrogates incorporated careful attention to capturing more than just the contents printed on the numbered pages of those issues. It stands to reason, then, that if the back of the wrapper had been present with the August issue that it would have been digitized. Perhaps it had been damaged and removed at some point. Yet sometimes mistakes happen. The only way to know for certain is to examine the original document.

Unfortunately, my teaching schedule will not allow me to visit the reading room at the American Antiquarian Society before publishing this entry. On the other hand, I am fortunate to live and work in the same city as the research library that houses the original magazine that was digitized to make the Royal American Magazine more widely accessible. That means that I have more ready access to the original and tracking down answers to these sorts of questions than most others who consult the images in the database. I will update this entry when time allow, but leave this discussion intact since it demonstrates that even though digital surrogates expand access, they cannot replace original sources.