What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

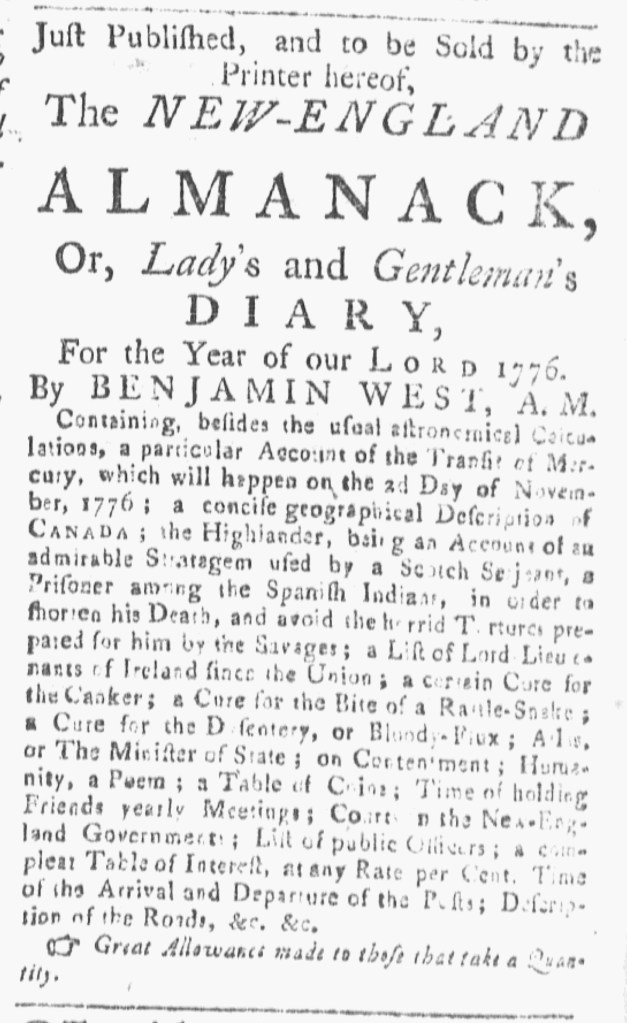

“Great Allowance made to those that take a Quantity.”

The collaboration between John Carter, the printer of the Providence Gazette, and Benjamin West, an astronomer and mathematician, continued for another year. An advertisement in the final issue of the Providence Gazette for 1775 alerted readers that the “NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK, Or, Lady’s and Gentleman’s DIARY, For the Year of our LORD 1776” by Benjamin West was “Just Published, and to be Sold by the Printer hereof.” At the end of the advertisement, a manicule directed attention to a note that informed shopkeepers and others of a “Great Allowance made to those that take a Quantity.” In other words, Carter offered steep discounts to retailers who purchased a significant number of copies to sell to their own customers. That pricing scheme allowed them to turn a profit by setting prices that competed with customers acquiring the almanac at the printing office.

To entice customers of every sort, Carter provided an overview of the contents of the almanac. In addition to the “usual astronomical Calculations,” it included “a particular Account of the Transit of Mercury, which will happen on the 2d Day of November, 1776.” Carter stoked anticipation for that event, making it even more appealing by providing those who purchased the almanac detailed information to help them understand it. The almanac also contained useful reference material, including “a Table of Coins, Time of holding Friends yearly Meetings; Courts in the New-England Government; List of public Officers; a compleat Table of Interest, at any Rate per Cent. Time of the Arrival and Departure of the Posts; [and] Description of the Roads.” The almanac also served as a medical manual with several remedies, such as “a certain Cure for the Canker, a Cure for the Bite of a Rattle-Snake; [and] a Cure for the Dysentery, or Bloody-Flux.” In addition to all that, the almanac had items selected to entertain or to educate readers, including a short essay “on Contentment,” “Humanity, a Poem,” and “a concise geographical Description of CANADA.” That last item may have been of particular interest given the American invasion of Canada in hopes of winning support for the American cause. Despite capturing Montreal in November, the attack on Quebec City failed in late December. American forces withdrew. The “concise geographical Description of CANADA” would not serve the intended purpose once word arrived in New England, though readers could consult it to supplement reports they read in the Providence Gazette and heard from others. Overall, Carter aimed to convince prospective customers that this almanac has an array of features that merited selecting it for use throughout the new year.