What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“They desire their old Customers and others to call at their Shop.”

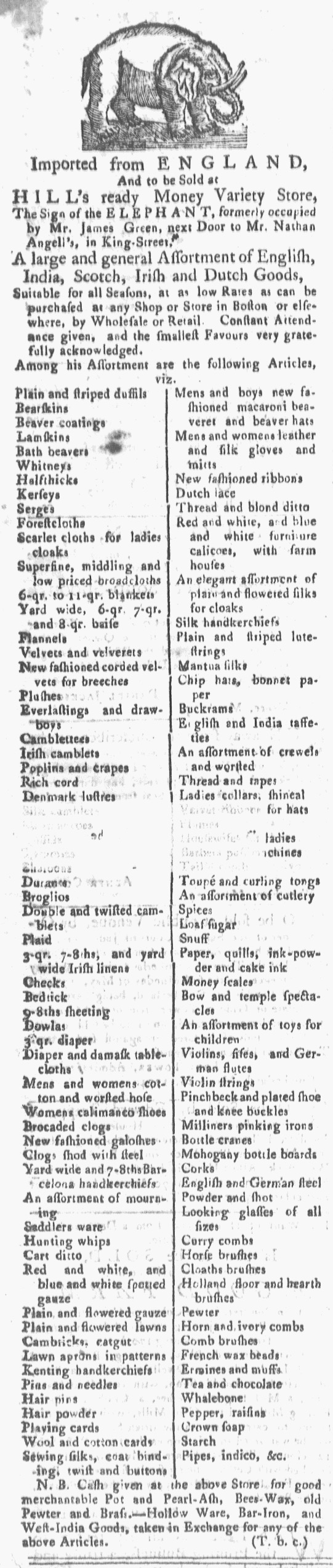

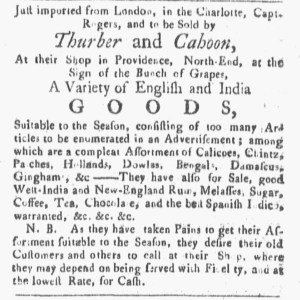

In the spring of 1774, Thurber and Cahoon advertised a “Variety of English and India GOODS” available at their shop “at the Sign of the Bunch of Grapes,” a familiar sight in Providence’s North End. They stocked items “Just imported from London, in the Charlotte, Capt. Rogers.” Merchants and shopkeepers often provided such information about the origins of their merchandise, allowing consumers to determine for themselves when they received their wares and whether items had been lingering on the shelves or in storerooms. Thurber and Cahoon, veteran advertisers, first placed this notice in the April 30, 1774, edition of the Providence Gazette. One of their competitors, Thomas Green, also received a shipment via the Charlotte. His advertisement for a “large and general Assortment of English and India GOODS” opened with similar copy: “Just imported in the Charlotte, Capt. Rogers, from London.”

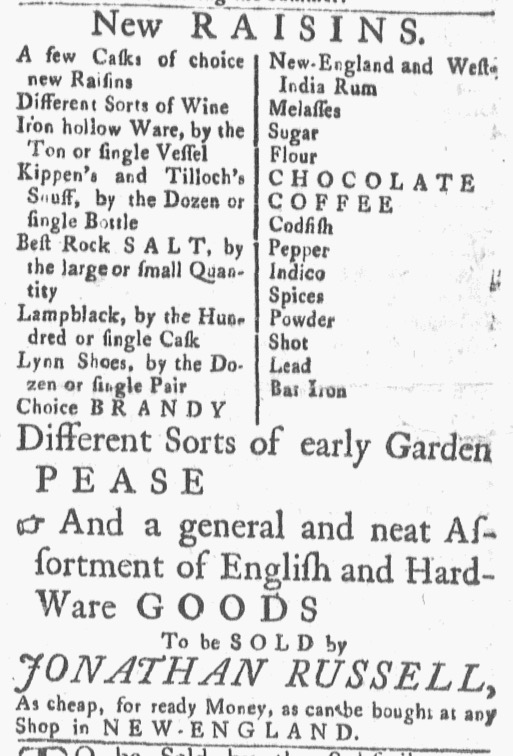

Thurber and Cahoon asserted that their new selection was “Suitable to the Season” and “consist[ed] of too many Articles to be enumerated in an Advertisement.” Merchants and shopkeepers often made such claims, encouraging prospective customers to view the merchandise for themselves. They promised an array of choices without going into details (and costing a lot more money for purchasing space in the newspaper). In contrast, “HILL’s ready Money Variety Store” continued running an advertisement that filled an entire column because it “enumerated” so many of the items for sale there, yet the proprietor could not claim that his wares just arrived. Thurber and Cahoon did spare a couple of lines for textiles, noting that they carried a “compleat Assortment of Calicoes, Chintz, Patches, Hollands, Dowlas, Bengals, Damascus, Gingham, &c.” The common abbreviation for et cetera suggested even more textiles that Thurber and Cahoon considered “too many” for their advertisement. They also mentioned several grocery items, including “Melasses, Sugar, Coffee, Tea, [and] Chocolate,” but did not specify when they received those items. In particular, they did not give specifics about when and how they received their tea, leaving it to prospective customers to determine if they wished to purchase that item even after reading about the politics of tea elsewhere on the same page of that issue of the Providence Gazette.

In a nota bene, Thurber and Cahoon made a final appeal, one intended especially for their existing clientele. “As they have taken great Pains to get their Assortment suitable to the Season” by acquiring goods consumers wanted or needed for late spring and the summer, the merchants declared, “they desire their old Customers and others to call at their Shop.” They pledged good customer service, stating that visitors to Sign of the Bunch of Grapes “may depend on being served with Fidelity.” They could also depend on finding bargains, paying the “lowest Rate” for goods, provided they paid in cash rather than credit. Thurber and Cahoon incorporated a variety of marketing appeals into an advertisement that occupied a single “square” of space in the Providence Gazette.