What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He has formerly attempted to get off for the West-Indies.”

In the 1760s the pages of the Georgia Gazette often included far more advertising concerning slaves – slaves for sale, runaway slaves, captured slaves – than advertising for consumer goods and services. These advertisements told the story of enslaved men, women, and children reduced to commodities to be bought and sold, but they also told stories of resistance to that dehumanization and commodification. Runaway advertisements testified to the agency, perseverance, and ingenuity of slaves who seized their freedom when they saw opportunities.

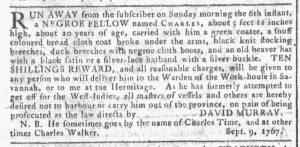

Much to his chagrin, David Murray told the story of one of those bold slaves, “A NEGRO FELLOW named CHARLES.” Although he was a young man, only “about 20 years of age,” Charles had previously attempted to escape from his master. While some slaves ran away with the intention of returning after a brief respite from their bondage, Charles had other plans. He did not seek temporary freedom but instead wished to permanently alter his situation. To that end, he had previously attempted “to get off for the West-Indies.” Murray did not offer any speculation to explain why Charles chose that destination; perhaps the young slave hoped to be reunited with family there. Whatever his reasons, Charles aimed to put considerable distance between himself and Murray, prompting the slaveholder to instruct “all masters of vessels” not to “carry him out of the province.” He also cautioned others “not to harbour” Charles, threatening to prosecute anyone who aided the fugitive.

To evade detection and capture, Charles adopted aliases, sometimes calling himself “Charles Time” and other times “Charles Walker.” Such resourcefulness may have aided in his escape and his ability to remain free for at least the month that had passed since Murray first placed his advertisement.

Between changing his name and making new efforts to escape even after his first attempt had been discovered, Charles demonstrated that he would not be subdued easily. While other advertisements treated enslaved men, women, and children as commodities – such as the “SIX FIELD NEGROES” or the “Young NEGROE WENCH” advertised for sale in the same issue of the Georgia Gazette – Murray’s advertisement about a “NEGROE FELLOW named CHARLES” underscored that slaves did not passively acquiesce to lives of perpetual servitude. Although certainly not Murray’s intent, his advertisement about a runaway slave told a powerful story of one man’s determination to fight to free himself from the injustices he experienced in colonial Georgia.