What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

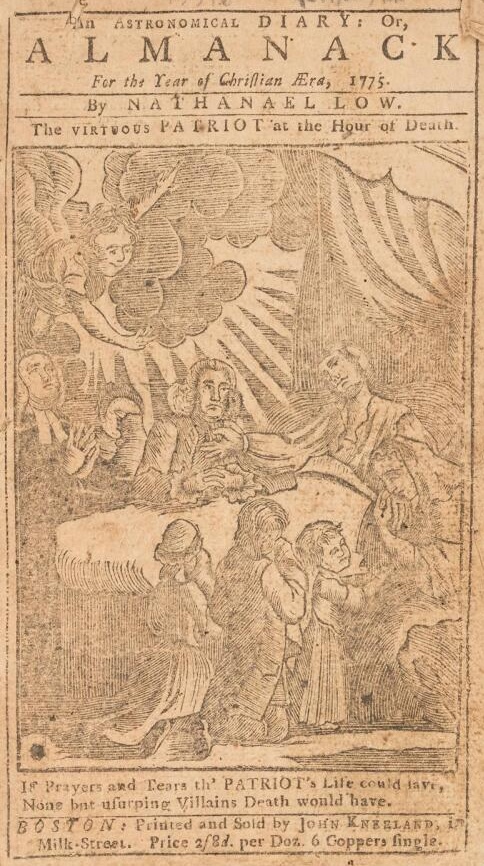

“ALMAN[A]CK … Ornamented with a large and elegant Engraving, representing the VIRTUOUS PATRIOT.”

When it came to buying almanacs, residents of Boston had many choices during the era of the American Revolution. That meant that printers often advertised what made the almanacs they published distinctive from others on the market. Such was the case for John Kneeland when he advertised Nathanael Low’s Astronomical Diary: Or, Almanack for the Year of Christian Aera, 1775 in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter in the fall of 1774. The production of the almanac and its promotion resonated with current events as the imperial crisis intensified. The Boston Port Act closed the harbor, the Massachusetts Government Act revoked the colony’s charter, and the other Coercive Acts punished the port city for the Boston Tea Party.

Kneeland informed prospective customers that this almanac was “Ornamented with a large and elegant Engraving, representing the VIRTUOUS PATRIOT at the Hour of Death.” In addition to the usual contents, “every Thing necessary in an Almanack,” it also included a “long and sympathetic Address to the Inhabitants of Boston, with several other Pieces of Speculation, which tends to rend it not only useful, but entertaining.” The engraving dominated the cover of the almanac. It depicted a man, the “VIRTUOUS PATRIOT,” on his deathbed. A woman, presumably his wife, and three children kneeled in the foreground. On the other side of the bed, a minister prayed while another man, perhaps a relative and likely another patriot, joined the family in their vigil. Above the bed, an angel welcomed the “VIRTUOUS PATRIOT” into heaven. A caption below the image stated, “IF Prayers and Tear th’ PATRIOT’s Life could save, None but usurping Villains Death would have.”

According to an auction catalog prepared by PBA Galleries, the “long and sympathetic Address” filled the first four pages of the almanac. Echoing rhetoric that circulated in newspapers and pamphlets, the address “rails against the British,” assuring residents of Boston that “[Your countrymen] are sensible the heavy hand of power under which you are now groaning is designed only as a prelude to the utter abolishment of American freedom.” The Coercive Acts, the address warned, would enslave the colonies to Britain. (Two advertisements on the same page as the advertisement for the almanac in the October 6, 1774, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston News-Letter concerned enslaved people, one presenting an enslaved woman for sale and the other offering a reward for the capture and return of an enslaved man who liberated himself by running away from his enslaver.) The address proclaimed, “My dear brethren, the destiny of America seems to be suspended on the present controversy; and it is on your fidelity, firmness, and good conduct, for which you have so remarkably signalized yourself on all occasions, that a happy issue of it in a great measure depends.” The advertisement for the almanac containing this address ran in the newspaper as the First Continental Congress continued its meetings in Philadelphia. A month earlier, the colonial militia in Worcester County to the west of Boston had closed the courts and removed British authority in what has become known as the Worcester Revolution of 1774. Six months after Kneeland advertised the almanac with the engraving and the address, a war for independence began with the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord.