What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“TEA and COFFEE every afternoon.”

Amid the turmoil over tea that included the Boston Tea Party in December 1773 and closure and blockade of the harbor via the Boston Port Act in June 1774, not all advertisers and consumers abstained from the problematic beverage, despite general calls for boycotting and destroying tea and newspaper editorials that condemned both the threat to liberty and negative effects on the body associated with drinking tea. Along with coffee, tea had become so much a part of dining, entertaining, and socializing that some entrepreneurs continued to include it among the amenities they offered to their customers in August 1774.

For instance, Edward Bardin, an experienced tavernkeeper, promoted tea when he “open’d the noted tavern at the corner house in the Fields … where ladies and gentlemen may depend upon the best entertainment and attendance.” In an advertisement in the August 11 edition of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, he advised that “The PANTRY opened every evening” with an array of items on the menu, including veal, mutton, duck, chicken, lobster, pickled oysters, custards, and tarts “of different KINDS.” Patrons could also rent a “large commodious ROOM, fit for balls or assemblies.” For those interested in a leisurely outing, Bardin served “TEA and COFFEE every afternoon.” Even though the political crisis intensified, he neither removed the troublesome beverage from his menu nor, apparently, believed that advertising it would lead to more trouble than it was worth. Not everyone lined up to take a principled stand against tea.

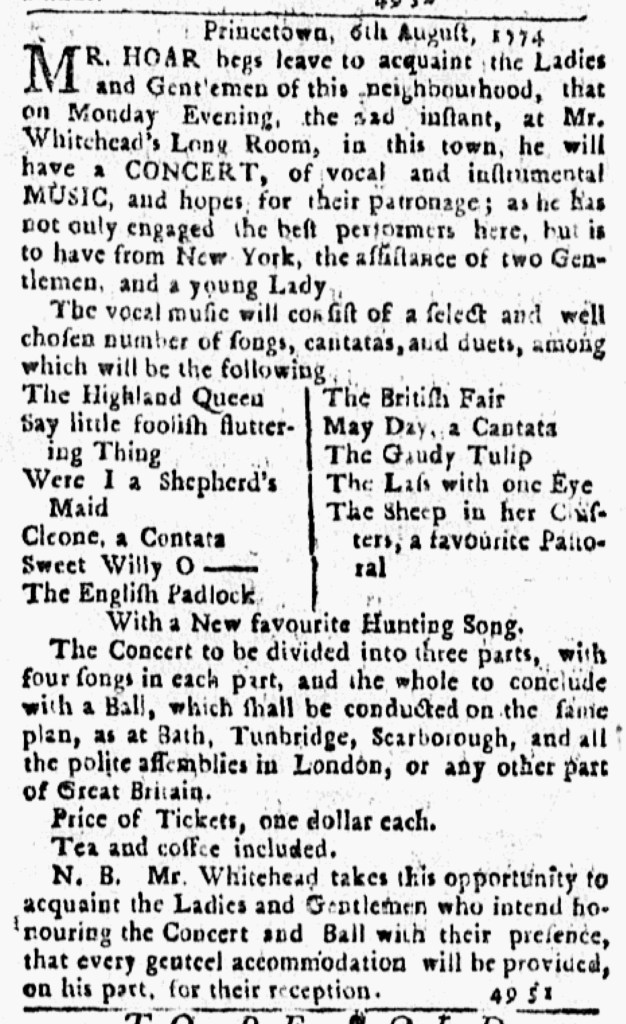

The same day that Bardin published his advertisement for the first time, Mr. Hoar of Princeton, New Jersey, inserted his own notice in the New-York Journal to invite readers in his town to attend a “CONCERT, of vocal and instrumental MUSIC” at “Mr. Whitehead’s Long Room.” He listed several “songs, cantatas, and duets” on the program. In addition, the concert would “conclude with a Ball, which shall be conducted on the same plan, as at Bath, Tunbridge, Scarborough, and all the polite assemblies in London.” The proprietor of the establishment, in a nota bene, promised that “every genteel accommodation will be provided.” Among those genteel accommodations, “Tea and coffee included” with each ticket. Neither Hoar nor Whitehead anticipated that serving tea would alienate so many people that it would be better not to mention the beverage. Instead, they made it a selling point in their advertisement. Did they face any ramifications for doing so? Perhaps growing public sentiment eventually encouraged more caution, but the tide had not turned against tea so much that some advertisers refused to include the drink as one amenity among many when they promoted entertainments to colonizers in the summer of 1774.