What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A VOYAGE to BOSTON: A POEM.”

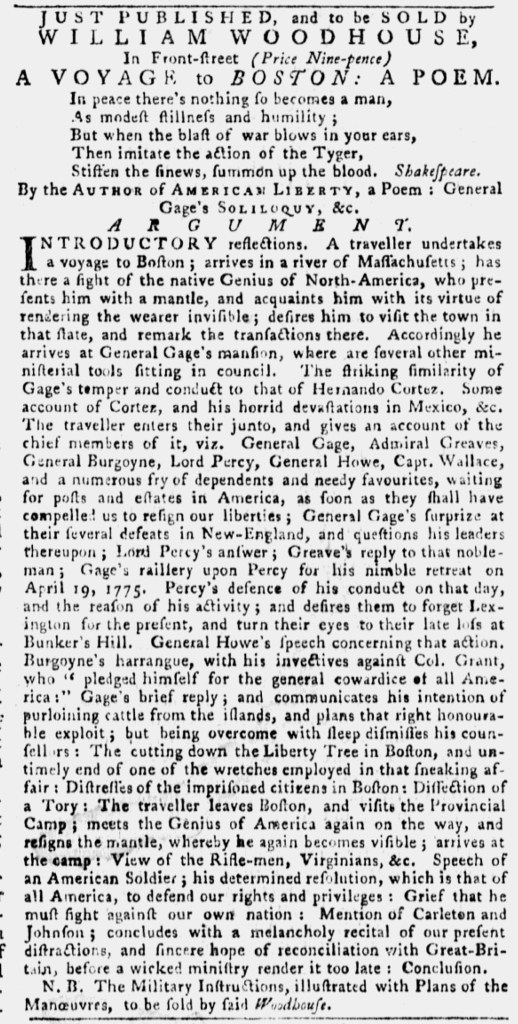

An advertisement for a new publication, “A Voyage to Boston: A Poem,” appeared on the front page of the November 18, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger. William Woodhouse, a bookseller, stationer, and bookbinder marketed a work that historians attribute to the pen of Philip Freneau and the press of Benjamin Towne. The imprint on the title page merely stated, “Philadelphia: Sold by William Woodhouse, in Front-Street.” The advertisement did advise that “A Voyage to Boston” was “By the same Author of AMERICAN LIBERTY: A Poem. General Gage’s SOLILOQUY, &c.” A similar note appeared on the title page. Woodhouse likely hoped that associating this publication with ones already familiar to readers would aid in inciting demand for the work. He also inserted five lines about peace and war from Shakespeare, transcribing them from the title page of the pamphlet.

Four days later, he published a much more extensive advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette. It contained all the content from the version in the Pennsylvania Ledger, including a nota bene that announced, “The Military Instructions, illustrated with Plans of the Manœuvres, to be sold by said Woodhouse.” The new advertisement also featured the “ARGUMENT” of the poem. That summary provided an overview of recent events as observed by an imaginary “traveller [who] undertakes a voyage to Boston” and, after being bestowed with a cloak of invisibility by the “Genius of North-America,” entered the city and witnessed General Thomas Gage and “several other ministerial tools sitting in council” as they discussed the battles at Lexington and Concord and “their late loss at Bunker’s Hill,” the “cutting down of the Liberty Tree in Boston,” and the “Distresses of the imprisoned citizens in Boston” as the siege of the city continued. The traveler departed from Boston, visited “the Provincial Camp,” returned the cloak, saw “the Rifle-men, Virginians,” and others who supported the American cause, and listened to the “Speech of an American Soldier,” delivered with “determined resolution, which is that of all America, to defend our rights and privileges.” The poem concluded with a “sincere hope of reconciliation with Great-Britain, before a wicked ministry render it too late.” Most colonizers still sought a redress of grievances rather than separating from the British Empire. In adding this lengthy “ARGUMENT” to the advertisement, Woodhouse did not compose original copy. Instead, just as the lines from Shakespeare came from the title page of the pamphlet, the “ARGUMENT” filled two pages of the pamphlet preceding the poem. Although he did not write the copy, Woodhouse apparently decided that providing more information about the contents of the poem would help to increase sales.