What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“People in the Country are already cautious of Counterfeits.”

On behalf of his partners, Richard Draper, printer of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter, placed an advertisement in the January 6, 1774, edition to inform the public that “Ames’s Almanack For the Year 1774, Is now in the Press, and will be ready for Sale” two days later, “on Saturday next.” Customers could acquire copies from Draper, Thomas Fleet and John Fleet, and Benjamin Edes and John Gill. On the following Monday, the Fleets, printers of the Boston Evening-Post, ran an updated version in the January 10 edition of their newspaper, announcing “THIS DAY PUBLISHED. Ames’s Almanack For the Year 1774.” That advertisement also listed all three printing offices. Edes and Gill, printers of the Boston-Gazette, ran a similar advertisement on the same day. Often competitors, those printers collaborated in publishing, advertising, and distributing the popular almanac.

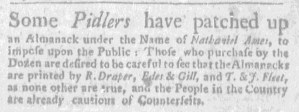

Just a few days later, however, Draper published a very different notice in the January 13 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter. “Some Pidlers,” he warned, “have patched up an Almanack under the Name of Nathaniel Ames, to impose upon the Public.” Someone not affiliated with those printing offices produced and disseminated counterfeit almanacs! Draper was especially concerned about the impact that would have on sales to retailers who purchased in volume to stock in their shops. “Those who purchase by the dozen,” he cautioned, “are desired to be careful to see that the Almanacks are printed by R. Draper, Edes & Gill, and T. & J. Fleet, as none other are true.” To encourage such vigilance, Draper asserted that “the People in the Country are already cautious of Counterfeits.” In other words, retailers better not think they could pass off the false almanacs to their customers because, according to Draper, those consumers knew which printers produced the authentic version and would not accept any other.

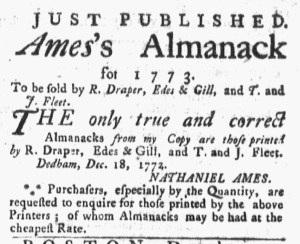

Although the notice did not indicate who printed the “Counterfeits” sold by the peddlers, Draper, the Fleets, and Edes and Gill faced competition for almanacs supposedly authored by Nathaniel Ames from printers in Boston (“Printed and Sold by E[zekiel] Russell”), Hartford (“Reprinted and Sold by Ebenezer Watson”), New Haven (“Reprinted and Sold by Thomas & Samuel Green”), and New London (“Printed and Sold by T[imothy] Green”). It was not the first time the partners encountered other printers attempting to infringe on what they considered their product to market exclusively. A year earlier, they advertised widely that they printed the “only true and correct ALMANACKS” by Ames, inserting a testimonial to that effect into their newspaper notices. The partners showed a similar concern for the effect on sales to retailers, directing “Purchasers, especially by the Quantity, … to be particular in enquiring whether they are printed by” Draper, the Fleets, and Edes and Gill. Several years earlier, on the other hand, they had been the counterfeiters. Almanacs generated significant revenue for early American printers, prompting them to print, to reprint, and to counterfeit the most popular titles.