GUEST CURATOR: Olivia Burke

Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

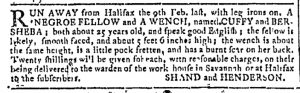

“RUN AWAY … CUFFY and BERSHEBA.”

Slavery advertisements were common in eighteenth-century newspapers, especially in the Georgia Gazette and other newspapers in southern colonies,. In the advertisement, Shand and Henderson offered a monetary reward for two of their slaves who ran away: Cuffy and Bersheba. They offered twenty shillings for each of them. This was one of six advertisements concerning slavery in this issue. In the Georgia Gazette, advertisements for slaves were just as common as advertisements for tea, household goods, and property for sale.

In a chapter on “Runaway Advertisements in Colonial Newspapers,” Victoria Bissell Brown and Timothy J. Shannon discuss how colonists saw slaves as material goods, not as human beings. “One of the great advantages to reading these advertisements in their original context is to comprehend how casually colonial Americans bought and sold human laborers.”[1] Based on the look inside colonial society that newspapers give us, we are able to see how colonists in the eighteenth century did not think twice about seeing an advertisement for a runaway slave next to one for a stray horse. As revolution drew closer to becoming a reality, slavery began to decline in the north but it remained strong in the south, where advertisements like this one were very common.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Olivia notes that in addition to Shand and Henderson’s notice about Cuffy and Bersheba making their escape, five other advertisements concerning enslaved men, women, and children appeared in the March 8, 1769, edition of the Georgia Gazette. Two of them reported on runaways that had been captured. Two offered enslaved people for sale, wile the final one offered an enslaved woman “To be hired out” as a domestic servant. When it came to such advertisements in the Georgia Gazette, this was actually relatively few compared to most issues. That newspaper often featured a dozen or more advertisements related to enslavement. They constituted an important source of revenue for James Johnston, the printer.

Olivia challenges us to consider how unremarkable white colonists found these advertisements that appeared week after week throughout the colonial period. This certainly reveals something significant about the attitudes of most colonists, but these advertisements also tell important stories about the experiences of enslaved people. Consider not only Cuffy and Bersheba but also their counterparts in the advertisements reporting Africans and African Americans who had been “TAKEN UP” or “”Brought to the Work-house.” Cuffy and Bersheba were both approximately twenty-five years old. Both spoke “good English,” indicating that they were either born in the colonies or had been transported there quite some time ago. When they made their escape, Cuffy had “leg irons on” (and Bersheba may have as well, though the wording of the advertisement does not make it clear). Shand and Henderson made every effort to keep them around, but Cuffy and Bersehba were determined to free themselves. Sampson, Molly, and an unnamed infant were discovered “on the Indian Country Path,” making their escape from a “master [who] lives near the salt water.” Sampson “speaks such bad English as scarcely to be understood,” suggesting that he may not have been enslaved his entire life. Michael, a “TALL STOUT ABLE NEGROE FELLOW” who had been confined to the workhouse in Savannah definitely had not been born into slavery in Georgia. He spoke little English. The advertisement reported that he was “of the Coromantee country” and had “his country marks thus ||| on each side of his face,” referring to ritual scarification.

Each of these advertisements provides a miniature and incomplete biography of enslaved people who attempted to seize their own liberty in the era of the American Revolution. White colonists placed them for one reason, recovering their human property, but these advertisements ultimately served an unintended purpose. They testified to the agency and resistance of enslaved men and women. Although not in their own words, these advertisements tell the stories of people who had few opportunities to create documents that recorded their own experiences.

**********

[1] Victoria Bissell Brown and Timothy J. Shannon, Going to the Source: The Bedford Reader in American History (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004), 48.