What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

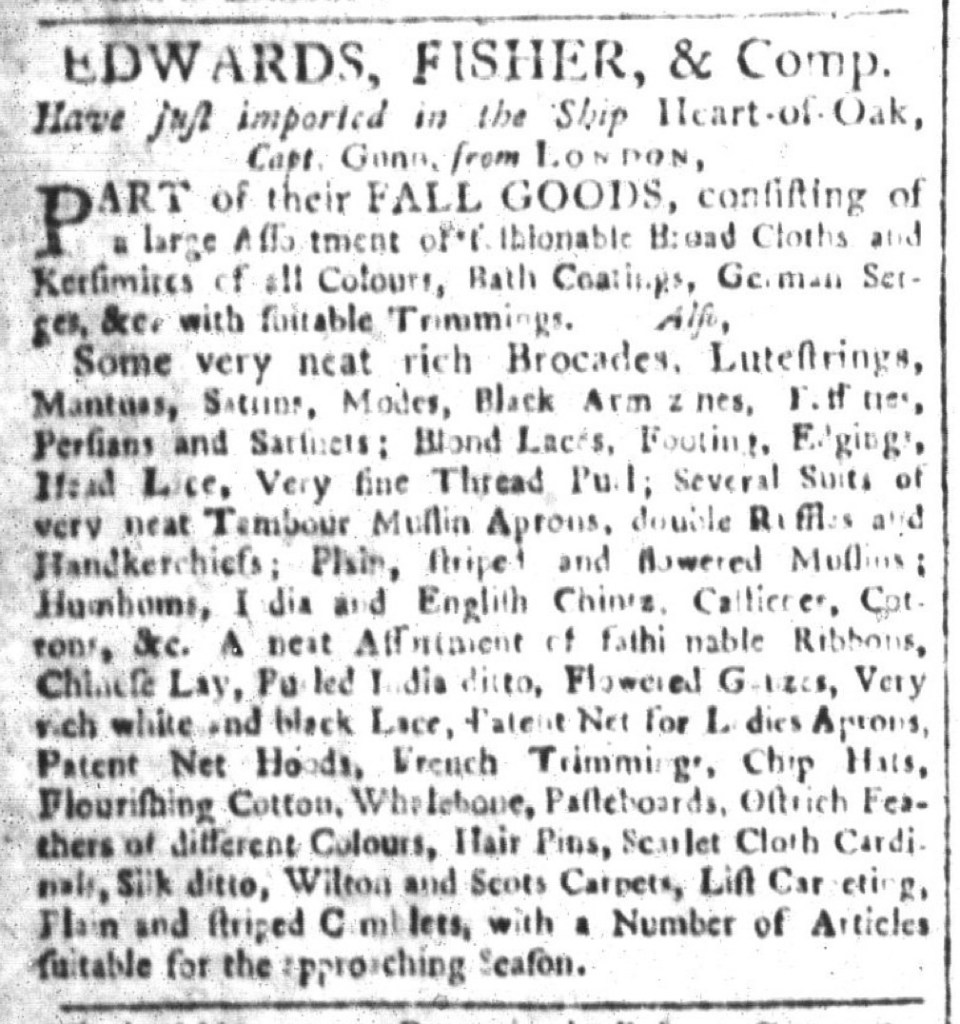

“Just imported … from LONDON, PART of their FALL GOODS.”

Like many other merchants and shopkeepers, Edwards, Fisher, and Company in Charleston updated their merchandise with the changing of the seasons. With the arrival of fall in 1774, they ran advertisements in the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, the South-Carolina Gazette, and the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal to announce that they had “just imported” a “large Assortment” of textiles and other items. This new inventory accounted for “PART of their FALL GOODS,” suggesting that they would continue to supplement their wares as ships arrived from London.

Edwards, Fisher, and Company may have believed that they had a narrow window of opportunity to import and sell these goods. Earlier in the month, a competitor acknowledged that “a Non-importation Agreement will undoubtedly soon take Place here,” encouraging consumers (“Ladies” in particular) to shop while they had the chance. The First Continental Congress had recently convened in Philadelphia to discuss coordinated measures in response to the Coercive Acts. Their deliberations would result in the Continental Association, a nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation agreement set to go into effect on December 1. In late September, merchants, shopkeepers, and consumers in Charleston and other American cities and towns did not yet know exactly which measures the First Continental Congress would adopt, but they reasonably anticipated that importing and purchasing goods would be constrained in the coming months.

That gave Edwards, Fisher, and Company an opportunity to sell the “Number of Articles suitable for the approaching Season” that had already arrived as “PART of their FALL GOODS.” They probably kept their fingers crossed that other shipments would arrive from London before news of a nonimportation agreement arrived from Philadelphia. They sought to entice prospective customers with an extensive list of their wares, describing them as “fashionable” more than once. What consumers would consider fashionable, however, evolved when nonimportation agreements went into effect. Homespun textiles produced in the colonies rather than “very neat rich Brocades” and other imported fabrics became fashionable because of the political principles they communicated. Edwards, Fisher, and Company would have to content with that another day; for the moment, they could continue following familiar strategies for marketing imported textiles and other goods.