What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

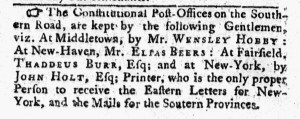

“The Constitutional Post-Offices on the Southern Road, are kept by the following Gentlemen.”

Although William Goddard established the Constitutional Post as an alternative to the British Post Office in 1773, advertisements for the service appeared in colonial newspapers only sporadically until after the battles at Lexington and Concord in April 1775. After the Revolutionary War began, however, the number and frequency of newspaper notices promoting the Constitutional Post increased, especially in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania. In May 1775, for instance, Nathan Bushnell, Jr., a postrider in Connecticut, stated that he was affiliated with the Constitutional Post in advertisements that ran in both the New-England Chronicle, published in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Connecticut Gazette, published in New-London. John Holt, the printer of the New-York Journal, inserted a lengthy advertisement to advise readers that a “Constitutional POST-OFFICE, Is now kept” at his printing office in early June.

An unsigned advertisement in the June 12, 1775, edition of the Connecticut Courant, published by Ebenezer Watson in Hartford, listed four branches: “The Constitutional Post-Offices on the Southern Road, are kept by the following Gentlemen, viz. At Middletown, by the Mr. WENSLEY HOBBY: At New-Haven, Mr. ELIAS BEERS: At Fairfield, THADDEUS BURR, Esq; and at New-York, by JOHN HOLT, Esq; Printer.” Holt may have been responsible for the notice, considering that it described him as “the only proper Person to receive the Eastern Letters for New-York, and the Mails for the Sout[h]ern Provinces.” One of the other postmasters could have placed the notice, though Watson may have done it of his own volition as a public service. Joseph M. Adelman persuasively argues that “printers had a direct financial and business interest in promoting a post office to their liking both because it distributed their newspapers and other print goods and because they were the chief beneficiaries of a patronage system centering on the post office.”[1] He also acknowledges that printers “enlisted merchants and members of the revolutionary elite … to provide financial and political support.”[2] The notice in the Connecticut Courant included only one printer, John Holt, among the four postmasters. Fairfield and Middletown did not have newspapers, but they did have need of reliable post offices and trustworthy postmasters. In New Haven, Thomas Green and Samuel Green printed the Connecticut Journal, yet the notice did not indicate that they had an affiliation with the Constitutional Post Office. While printers played an important role in establishing the service, they worked alongside postmasters from other occupations in creating an infrastructure for disseminating news and information.

**********

[1] Joseph M. Adelman, “‘A Constitutional Conveyance of Intelligence, Public and Private,’: The Post Office, the Business of Printing, and the American Revolution,” Enterprise and Society 11, no. 4 (December 2010): 713.

[2] Adelman, “Constitutional Conveyance,” 709.