GUEST CURATOR: Kamryn Vasselin

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

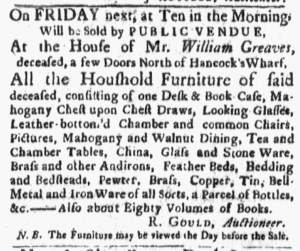

“Will be Sold … Brass and other Andirons, Feather Beds.”

This advertisement features a variety of household goods sold at an auction held by R. Gould after the death of William Greaves. What caught my eye about this advertisement was some of the items being sold, like andirons and feather beds. I was not familiar with these items before reading this advertisement.

Andirons are a pair of brass or iron bracket supports used to hold up logs in an open fireplace. Andirons allow for better burning and less smoke due to the air circulation underneath the wood. In 1775, most homes used wood-burning fireplaces to keep warm, especially during cold winters. The use of andirons was widespread during this time.

The other item that caught my eye was featherbeds. According to art historians interviewed by Sunny Sea Gold, many people slept on beds of several different layers during this time. She reports, “At the bottom was a simple, firm mattress pad or cushion filled with corn husks or horsehair. Next came a big featherbed for comfort.” We would equate these to mattresses today, just instead filled with feathers. These featherbeds often sagged and caused problems when people laid flat on them. Wealthier colonists could buy professionally made featherbeds, while those less fortunate usually made their own out of goose or duck feathers.

Goods being sold at an auction as part of an estate sale generally cost less than when bought new. For those who may have needed a pair of andirons but were unwilling or unable to spend much, seeing this advertisement would have likely drawn them to the auction to get a good deal. The same goes for the featherbed, even a used one. An opportunity to increase the comfort of their bed at a cheap price would have provoked the interest of many people.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

When I invite students to serve as guest curators for the Adverts 250 Project, I do so in hopes that they will immerse themselves in eighteenth-century life and culture in new ways. I assign both primary sources and secondary sources for our classes, yet I want my students to examine some aspect of life in early America even more intensively. That begins with compiling a digital archive of newspapers published during a particular week during the era of the American Revolution and continues with searching through those newspapers to select advertisements that interest them.

Seeing why different advertisements spark interest for different students is always an interesting and illustrative part of working on this project together. I learn from my students, especially when they explain what they see in their advertisements as they work with early American newspapers for the first time compared to the assumptions that I make after reading those newspapers for years. I appreciate how Kamryn took an advertisement that would have appeared plain and ordinary to eighteenth-century readers familiar with the material culture of the period and demonstrated that some of the everyday items that colonizers purchased and used are no longer everyday items in the twenty-first century. As a result, they require some explanation to understand their purpose and significance in the eighteenth century.

I also appreciate that Kamryn commented on auctions as the way that consumers sometimes acquired those objects of everyday life. R. Gould, one of several auctioneers in Boston, oversaw an estate sale at the home of William Greaves. The advertisement for that auction appeared between notices for upcoming sales at “RUSSELL’s Auction Room in Queen street” and William Hunter’s “New Auction-Room, Dock-Square.” Some of the items for sale at “Hunter’sAuction-Room” were certainly secondhand goods, like at the estate sale, being the “Property of a Gentleman leaving the Province,” yet others, as far as the advertisements revealed, were new. As Kamryn notes, auctions offered bargains to consumers, whether they purchased new or used goods.