GUEST CURATOR: David Alexander

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

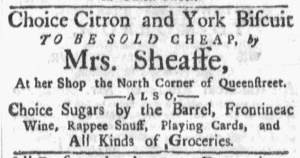

“TO BE SOLD CHEAP, by Mrs. Sheaffe.”

Mrs. Sheaffe placed this advertisement in the Boston Evening-Post. She ran a shop where she sold a variety of items, including choice citron (referring to citrus fruits), sugar, wine, and “All Kinds of Groceries.” Mrs. Sheaffe ambitiously invested to integrate herself into life as a businessowner as her advertisements appear twice in Massachusetts newspapers during the week of January 14-20, 1774, appearing in both the Boston Evening-Post and the Boston-Gazette. According to Gloria Main in “Gender, Work, and Wages in Colonial New England,” “most women in retailing were widows who had taken over a deceased husband’s shop.”[1] As this woman went by “Mrs. Sheaffe” it is likely that she was a widow and opened her shop to support herself and her family. Mrs. Sheaffe’s investments in advertising her shop in multiple newspapers demonstrates her industriousness and desire to establish herself as a businessowner of Boston. During the Revolutionary Era, the role of women in business extended far beyond just buying goods, many of them acting as retailers themselves.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

David convincingly suggests that Mrs. Sheaffe may have been a widow responsible for supporting herself and perhaps others in her household. When other female entrepreneurs placed advertisements in newspapers published in Boston, they tended to use their full names, just as their male counterparts did. Mrs. Sheaffe’s decision to go by “Mrs. Sheaffe” may have been intended to remind those who knew her of her circumstances as a widow. She may have also meant for that to justify her role in the marketplace as a shopkeeper rather than as a consumer. Although some women ran businesses, as their advertisements attest, doing so was often depicted as a masculine endeavor, one better suited to men than women.

Mrs. Sheaffe attained a certain level of visibility in Boston, thanks in part to her frequent advertisements. Other women certainly assisted in running family businesses, even when they were not considered proprietors or mentioned in advertisements. When Herman Brimmer and Andrew Brimmer advertised “An Assortment of Mens, Womens & Childrens Hose” and other garments in the same edition of the Boston Evening-Post that Mrs. Sheaffe promoted her wares, they sought female customers, recognizing the role that women played as consumers. Their advertisement, like so many others, may have hidden the role that wives, daughters, and other female relations played in helping to run their shop “next Door to the Sign of the Lamb.”

Other female entrepreneurs did not achieve the same visibility in the marketplace as Mrs. Sheaffe because women were less likely to place newspaper advertisements compared to men who ran businesses. That same issue of the Boston Evening-Post included a notice calling on “All Persons indebted to the Estate of the late Mrs. Ruth Sinclair, Shopkeeper,” to settle accounts. According to a list of recent deaths in the December 27, 1773, edition of the Boston Evening-Post, she was the “Widow of the late Capt. Sinclair.” He died thirteen years earlier, a notice about settling his estate in the August 25, 1760, edition of the Boston-Gazette listing his widow as “sole Executrix.” Although she was apparently known to residents of Boston as a shopkeeper, Ruth Sinclair did not publish any advertisements. Instead, she may have relied on foot traffic and recommendations from loyal customers.

Mrs. Sheaffe was not alone as a proprietor of her own business during the era of the American Revolution. Other women ran businesses and an even greater number participated in the marketplace as more than consumers, assisting in shops run by husbands, fathers, brothers, and others. Yet Mrs. Sheaffe did make her role as a female entrepreneur much more visible in the public prints than most other women. Her advertisements testify to what was possible for women, though not usual.

**********

[1] Gloria L. Main, “Gender, Work, and Wages in Colonial New England,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 51, no. 1 (January 1994): 58.