What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“YES, YOU SHALL BE PAID; BUT NOT BEFORE YOU HAVE LEARNED TO BE LESS INSOLENT.”

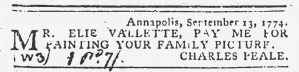

The saga continued. Elie Vallette, the clerk of the Prerogative Court in Annapolis and author of the Deputy Commissary’s Guide, did not bow to the public shaming that Charles Willson Peale, the painter, undertook in the pages of the Maryland Gazette in September 1774. Earlier in the year, Peale had painted a family portrait for Vallette and then attempted through private correspondence to get the clerk to pay what he owed. When Vallette did not settle accounts, Peale turned to the public prints. He started with a warning shot in the September 8 edition of the Maryland Gazette: “IF a certain E.V. does not immediately pay for his family picture, his name shall be published at full length in the next paper.” Peale meant it. He did not allow for any delay in Vallette taking note of the advertisement and acting on it. A week later, he followed through on his threat, resorting to all capitals to underscore his point, draw more attention to his advertisement, and embarrass the recalcitrant clerk. “MR. ELIE VALLETTE,” Peale proclaimed in his advertisement, “PAY ME FOR PAINTING YOUR FAMILY PICTURE.”

That still did not do the trick. Instead, it made Vallette double down on delaying payment. He responded to Peale’s advertisement, attempting to put the young painter in his place. In a notice also in all capitals, he lectured, “MR. CHARLES WILSON PEALE; ALIAS CHARLES PEALE – YES, YOU SHALL BE PAID; BUT NOT BEFORE YOU HAVE LEARNED TO BE LESS INSOLENT.” Vallette sought to shift attention away from his own debt by critiquing the decorum of an artist he considered of inferior status. That strategy may have worked, though only for a moment. Peale’s advertisement did not run in the next issue of the Maryland Gazette. That could have been because Peale instructed the printer, Anne Catharine Green, to remove his notice and returned to working with Vallette privately. Even if that was the case, it was only temporary. “MR. ELIE VALLETTE, PAY ME FOR PAINTING YOUR FAMILY PICTURE” appeared once again in the October 6 edition. Peale was not finished with his insolence. He placed the advertisement again on October 13 and 20. Vallette did not run his notice a second time, perhaps considering it beneath him to continue to engage Peale in the public prints. He had, after all, made his point, plus advertisements cost money. That being the case, the painter eventually discontinued his notice. Martha J. King notes that Vallette “eventually settled his account about a year later.”[1] For a time, advertisements in the only newspaper printed in Annapolis became the forum for a very public airing of Peale’s private grievances and Vallette’s haughty response.

**********

[1] Martha J. King, “The Printer and the Painter: Portraying Print Culture in an Age of Revolution,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 109, no. 5 (2021): 79.