What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

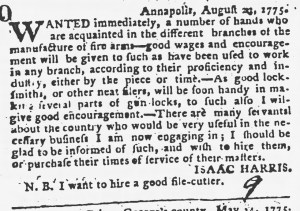

“WANTED immediately, a number of hands who are acquainted in the different branches of the manufacture of fire arms.”

In the late summer and early fall of 1775, Isaac Harris took to the pages of the Maryland Gazette with a call for “a number of hands who are acquainted in the different branches of the manufacture of fire arms.” The timing of Harris’s advertisement, dated August 23, coincided with a new stage of the imperial crisis that started more than a decade earlier when Parliament attempted to regulate trade with the colonies following the conclusion of the Seven Years War. The crisis had intensified at various moments, including passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 and imposition of duties on certain imported goods via the Townshend Acts in the late 1760s. Events in Boston had often fueled the crisis, including the Boston Massacre in March 1770 and the destruction of tea by dumping it into the harbor in December 1773. Parliament responded with the Coercive Acts, including the Boston Port Act and the Massachusetts Government Act, to punish the unruly Patriots, yet colonizers in other places believed that they could also be subject to similar treatment.

Yet only recently had hostilities commenced when Harris composed his advertisement and submitted it to the printing office in Annapolis. News of the battles at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the ensuing siege of Boston, the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, and the appointment of George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army inspired colonizers to make preparations to defend their liberties. Harris may have been among their ranks as he set about making firearms in Maryland. He offered “good wages” to workers with experience in any aspect of producing firearms, paying them “according to their proficiency and industry, either by the piece or time.” In addition, he thought that “good locksmiths, or other neat filers, will be soon handy in making several parts of gun locks.” Colonizers with experience in other occupations could apply their skill to this endeavor. Harris also sought indentured servants to join this enterprise, offering to hire them or “purchase their times of service [from] their masters.” According to his advertisement, Harris planned to make a significant investment in acquiring the labor to support what he called “the necessary business” of making firearms. Readers almost certainly made a connection between Harris’s plan to make firearms and the events that continued to unfold in Massachusetts.