What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

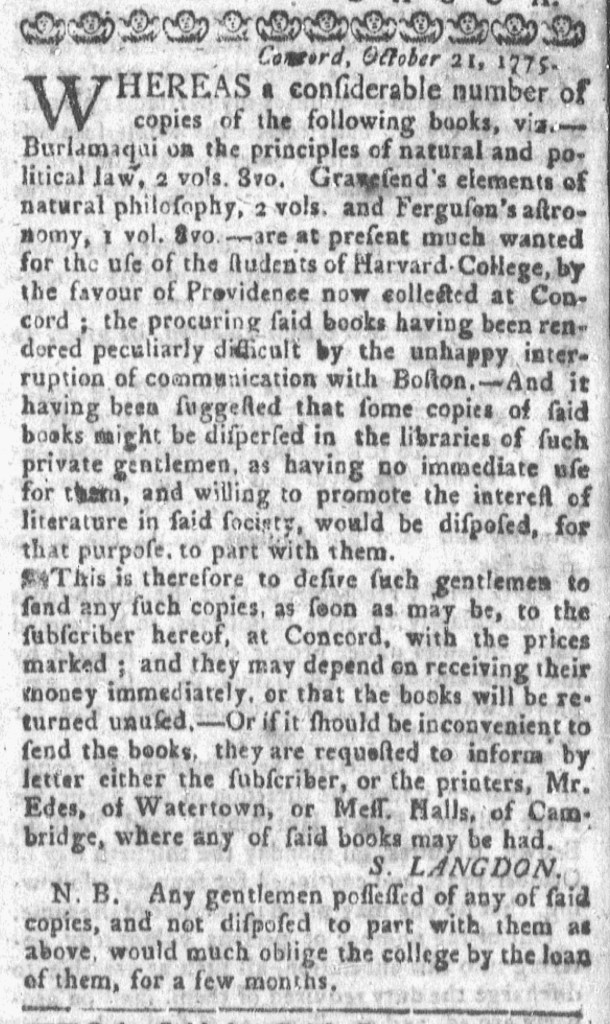

“The following books … are at present much wanted for the use of the students of Harvard College.”

Samuel Langdon, the president of Harvard College, issued a plea in the fall of 1775. His students needed books! As he explained in his advertisement in the November 6, 1775, edition of the Boston-Gazette, the college held classes in Concord while the siege of Boston continued … yet students could not acquire many of the texts that they needed because of “the unhappy interruption of communication” and trade with booksellers (and other purveyors of goods and services) in Boston. Similarly, Benjamin Edes had moved the Boston-Gazette to Watertown following the battles at Lexington and Concord.

Langdon sought “a considerable number of copies” of “Burlamaqui on the principles of natural and political law, 2 vols. 8vo. Gravesend’s elements of natural philosophy, 2 vols. And Ferguson’s astronomy, 1 vol. 8vo.” In specifying both the number of volumes and the size (“8vo” or octavo) of the books, Langdon made clear that the college preferred certain editions. He reported that others “suggested” to him “that some copies of said books might be dispersed in the libraries of such private gentlemen” who did not have immediate use for them and thus might be willing to “part with them” to “promote the interest of literature” among the youth attending Harvard College.

Langdon requested that “such gentleman” who did have those books “send any such copies, as soon as may be … with the prices marked.” They could “depend on receiving their money immediately, or that the books will be returned unused.” Langdon understood that some readers might not wish to part with volumes from their personal libraries. Alternately, he suggested that that it would “much oblige the college” if they would loan those volumes “for a few months.” With classes continuing despite the disruptions caused by the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord the previous spring, Langdon engaged in an eighteenth-century version of crowdsourcing in his effort to procure books for his students. The college survived a fire in its library a decade earlier, requesting donations of books to recover. Now Harvard faced other obstacles and once again turned to the public to provide the books that the college needed.